Biking The Forgotten Canal Du Midi: Day 1

Our 5-day bike trip took us across this troubled but spectacular monument.

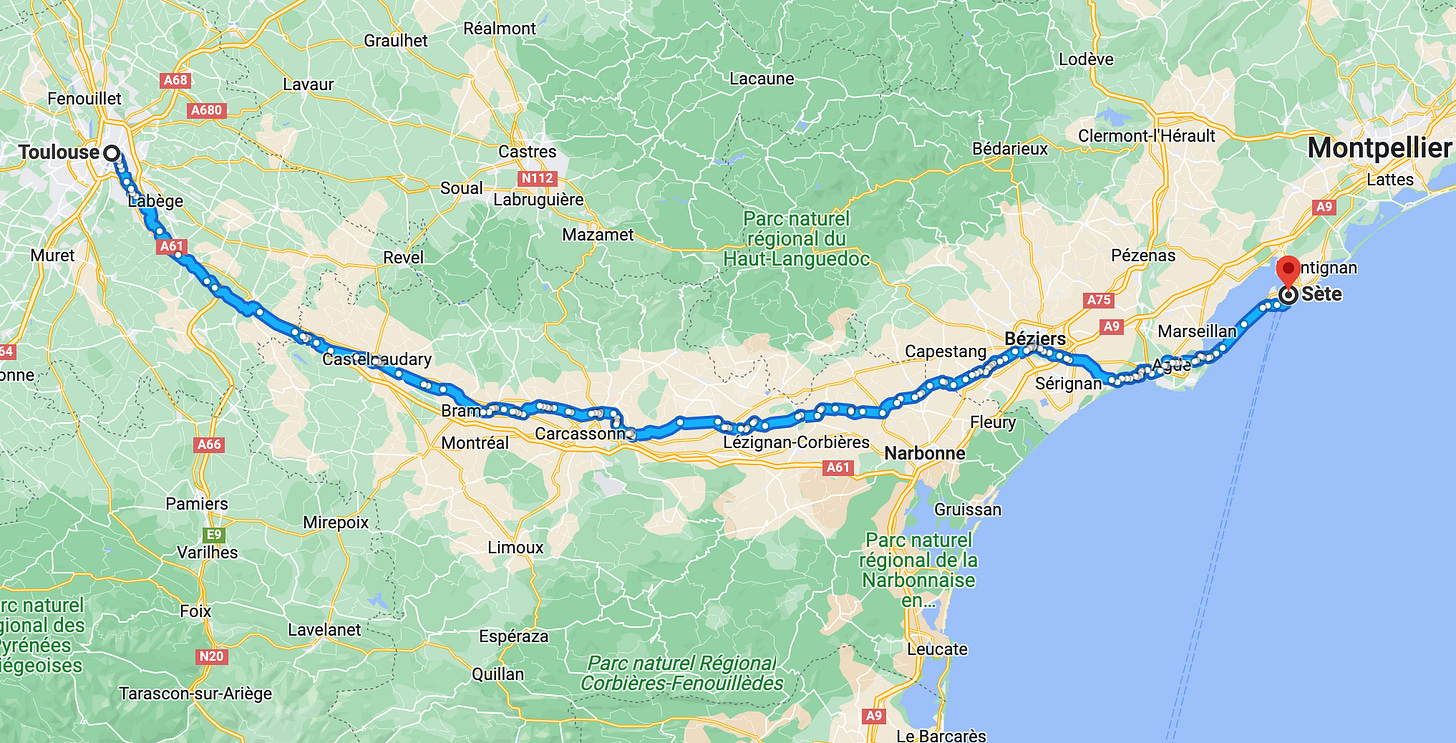

King Louis XIV’s desire to embrace projects of grandeur in the 17th century left a legacy in France that includes the Chateau de Versailles and the Canal du Midi. Three centuries later, the two monuments have taken very different paths. Readers have no doubt heard of the first, but much less likely the second. Versailles remains a gleaming if garish jewel that draws hordes of international tourists. In contrast, the canal that stretches 150 miles across the southwest of France linking Toulouse to the Mediterranean Sea has grown tarnished from neglect and disease ravaging its signature canopy of trees lining its banks.

While the canal may have fallen into obscurity outside the Southwest, it was ever-present in our daily lives, passing not far from our apartment in Toulouse and slicing an arc around the city center. At the mid-point in town, it passes under the vigilant eye of a white marble statue honoring its creator, Baron Pierre-Paul Riquet. A warm weekend afternoon often drew us to the canal’s banks for a walk or a bike ride.

After numerous such outings, and increasingly curious about the canal, we decided to embark on a 5-day trip to traverse the waterways to its coastal end during the April 2018 school holidays.

Once Upon A Canal

The canal was one of the world’s engineering marvels at the time of its construction in the 17th century. Yet when I would mention to Paris friends that we were preparing for this trip, they would give me a puzzled look as if they were searching their memory banks for some reference point. Sometimes I found myself in the odd position of explaining this piece of their country’s history and geography to them but never really succeeding in conveying its allure.

Making such a trip sounded ambitious for a family of two middle-aged adults and two teenagers who were far from top biking condition. But the route is mostly flat, beginning with only the slightest of ascents and then descending gradually almost until the end. Trees lining the canal promised shade. And a regular interval of towns along the way offered plenty of flexibility in terms of the distance we would cover each day.

Still, our research hinted at some of the challenges awaiting us. Reliable English-language guidebooks or internet sites were hard to come by, and the French ones made references to the impassibility of certain stretches or the need to look for hard-to-spot signage to know when to change sides of the canal. The lack of a maintained bike path and clear tourist information was particularly surprising in France where tourism fuels the economy. Cities and regions of all sizes churn out massive promotional campaigns to attract visitors to the most minor of historic or cultural attractions. That somehow a genuine attraction such as the Canal du Midi had failed to warrant such comprehensive marketing attention and investments in tourism infrastructure seemed like a massive missed opportunity.

Even with these advanced warnings, we were still troubled at times by the state of much of the canal that was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996. Thousands of disease-ridden trees that give the canal its distinctive canopy have been ripped out, with more cuttings planned as boosters search for funds to replant new ones. Perhaps even more ominous, the effects of climate change and regional growth are putting pressure on the complex water system that feeds the canal, which shares these water resources with local farmers and residents.

For all these dark clouds over its future, our trip along the canal still managed to instill a sense of its wonder and majesty. The Canal du Midi holds enormous potential to be the perfect ambassador for this region’s history, cuisine, and culture. Our five days of pedaling along its banks offered a chance to intimately discover the beauty that surrounds it and appreciate the passion and innovation that was required to build it. If it can be made more accessible to less adventurous riders, the Southwest of France could unlock a true treasure. “It’s completely forgotten,” Olivier Auriol, chief of Canal du Midi projects for the local Haute-Garonne government, told me. “We know it is exceptional and its history is important. But that has not been enough to ensure its notoriety.”

Basket Cases

As tends to happen when living abroad, the obstacles appeared well before the trip. Bikes were our first priority. The previous year we had taken a 4-day bike trip across the Loire Valley in central France, a region where the biking economy is massive and companies that rent and organize your journey are plentiful. While renting in the Loire had been easy, we found the Canal du Midi offered few choices of rental options and limited flexibility. We decided instead to buy bikes.

A local sporting goods store was having a sale, so we purchased four gray and black Riverside 900 hybrid bikes. Such tasks are easily managed in the U.S., but in France, this required additional vocabulary which we had not thought to master in advance.

For example, in the U.S. the saddlebags that hang on the back of the bikes are called panniers, a mild corruption of panier, the French word for basket. Easy enough, we thought. Here’s a word we actually know! But when we kept telling the salesperson we wanted paniers, they gave us funny looks and kept explaining that it didn’t make sense for long bike trips. We kept insisting and resorted to hand gestures that probably looked vaguely obscene until a light went on. “Ah, you want sacoches,” a salesperson said and led us to the aisle where the saddlebags were found. In France, a panier is specifically the front basket.

We bought 2 sets of sacoches that could carry up to 30 pounds each and put them on the adult bikes to ease the burden on our teenage kids. This required precision packing in the days before the trip, limiting clothing changes, toiletries, and optional items like books to make sure we also had room for nonperishable snacks, a first aid box, and a minimalist bike repair kit. After much packing, unpacking, and re-packing and long debates about what constituted “essential” items, we had the bags stuffed, just to the point of being able to close them.

The day of the departure was a glorious April morning, blue skies without a hint of clouds. The itinerary for the first day called for riding 33 miles through a stretch that would climb almost imperceptibly about 175 feet. While this didn’t require vigorous pedaling, it also didn’t allow for much coasting.

After mounting the sacoches on the bikes, and checking everyone’s gear one last time, launching on this epic adventure meant simply rolling out from our apartment’s courtyard through the tunnel that leads to the massive wooden doors which open onto the street. After a quick right turn, we glided past the neighborhood’s red-bricked buildings. Just 5 minutes later, we reached the banks of the canal.

Turning southeast, the paved path ran along the right side of the canal. The canal’s reflective waters stretch about 60 feet across, met by sloping banks on each side. In Toulouse, the bike path that runs alongside has the feel of a festive city park. Parents pushing strollers, couples holding hands, and distracted singles walking their dogs while staring at their smartphones. Progress was slow as we zigzagged our way through the crowds while constantly ringing our bike bells, a task made awkward as we adjusted to the weight of the sacoches.

As we dodged pedestrians, we passed a series of péniches, the flat, 128-foot-long barges that were specially designed for the canal and its locks. These workhorses once ferried all sorts of goods up and down the canal and today are a reminder of an era when the canal was a far more vital economic engine for the southwest of France. Today, many have been refurbished into restaurants, tour boats, and in some cases houseboats.

Overhead, we were protected by the vaulting platanes, the trees with light-gray colored trunks and soaring branches that stretch out over the canal and cross with their siblings on the other bank, forming a spectacular canopy. This is the iconic view of the Canal du Midi, running for long stretches and featured in just about every postcard. We were grateful for the shade it offered, and the sense that we had entered into a world apart from the city that was slowly slipping away behind us. Eventually, the crowds thinned, and we found a rhythm that was both peaceful and exhilarating.

About 8 miles into the ride, we passed our first lock, the Écluse de Castanet. Two ivy-covered stone walls reached out from each bank toward the middle, where they supported two metal doors about 20 feet high. A red light signaled to boats traveling the same direction that the écluse was closed and filled with water to allow boats coming from the other direction to enter and descend. We climbed a short hill along the canal that brought us to the top of the écluse. On the other side of the metal doors, the stone walls bowed outward in the middle and then narrowed again around another set of doors.

Along the side of the path was a former customs house that had been converted to a restaurant bearing the name of the écluse. Already sweaty and trying to catch our breath, we looked with envy onto the terrace where patrons were sipping wine and idly cutting into their steak with pepper sauce. (We went back later on bikes later and enjoyed a wonderful lunch here).

There are 65 écluses along the canal, with some of their customs houses converted into B&Bs, snack shops, or restaurants of some kind. While the écluses have all been replaced in recent decades, the original ones were one of the key breakthroughs by Riquet, the 17th-century baron and tax collector whose combination of money, madness, and genius created the canal.

Such a canal had long been a fantasy in France, a way to leverage commerce from the Mediterranean while also avoiding the pesky Spaniards and pirates to the south. Such notable names as Leonardo Da Vinci had taken a stab at the project but ultimately threw up their hands. It was Riquet of Béziers who proposed a workable plan that convinced King Louis XIV and his ministers to give the go-ahead in 1666. The king was enamored with the idea of sponsoring great engineering projects that would suggest the kind of technical daring that allowed the Romans to build aqueducts that can still be found throughout France today.

Riquet succeeded by solving two major problems. First, he created a system that drew water from the region’s Black Mountain to the north and funneled it into the canal. He did this initially by constructing a damn about 12 miles north of the town of Castelnaudary and creating Lake Saint-Ferréol, the largest such reservoir ever built in Europe at the time. The water runs downhill toward Port Lauragais, near the canal’s highest point. He also worked with his engineering team to design the hydraulic locks that used swinging doors and valves to fill and release water to move boats up and down the canal. While the French king agreed to underwrite the project along with the regional government, Riquet financed 20% of the project in exchange for ownership of the canal. A tax levied on trade was expected to generate huge returns for all.

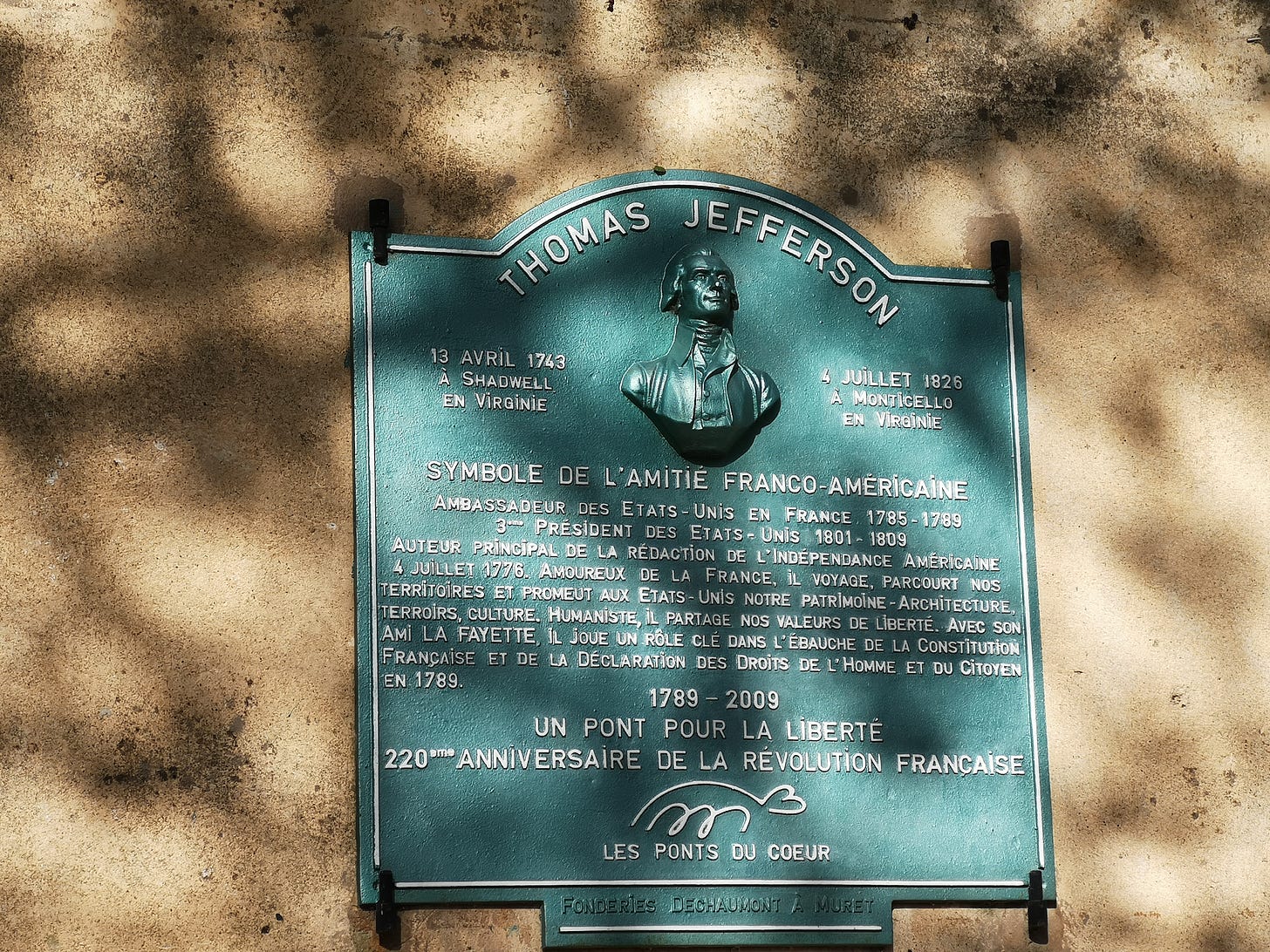

Not surprisingly, numerous problems arose. Even with Riquet’s crew coming up with solutions, such as carving out a tunnel or aqueduct when needed, construction dragged on. Riquet died in October 1680, just a few months before the canal was officially opened in 1681, having spent nearly his entire fortune. Such was the grandeur of the endeavor that Ambassador Thomas Jefferson, traveling the canal in 1787 from its end up to Toulouse where it eventually was connected to the Garonne River that flowed to Bordeaux, was in awe of what was then called the Canal Royal du Languedoc.

Today, nearly all of the écluses sport an engraving saluting Jefferson’s journey up the canal. We read them to learn this bit of our own history whenever we paused at various customs houses for bathroom breaks, to replenish water, or for short picnics.

As we neared the end of Day 1, things had been remarkably tranquil, without any major incidents, and our gang of four was still in good spirits. We had worried about the kids’ attitudes and motivation toward this biking adventure, but instead found them so energized that our main problem was them racing far ahead and out of sight. The adults had a more measured pace, plus most of the gear, and we had to push ourselves to close the gap.

After about 5 hours of riding, we arrived at our hotel for the evening, a péniche called Kapadokya. Almost 100 feet long and 15 feet wide, the boat was built in Belgium back in 1939 and passed through several hands before being purchased by the current owners, Mado and Patrick Isaac. The hull was painted deep black, with the sideboard of the deck and a terrace painted a striking red, and sporting a large red and gold Occitanie flag over the bow. We crossed the canal on a small stone bridge to the other bank where the péniche was moored, locked our bikes, and were greeted by Mado, a short and energetic woman.

It was surprisingly spacious below deck, with one master bedroom for us that also had a shower and a slightly smaller 2-bed room adjacent to ours for the kids. After relaxing for a bit, we climbed back on deck at a table where we made an improvised dinner of the last of our provisions, including some cheese, ham, baguette, avocado, tomatoes, and Cliff Bars for dessert. Hardly the meal of kings, but we had worked hard for it and savored every bite as the sun set and applauded ourselves for having successfully navigated the first day.

Tomorrow: Day 2

Chris O’Brien

Le Pecq

We cycled the Canal over five days five years ago when I’d just turned 70. We are fit leisure cyclists and this wasn’t easy. Parts were two feet deep in mud after previous heavy rain and others the path was 6” wide with grass growing way over our heads. We were told it normally takes 7 days but we only had 5 so it wasn’t a relaxing sightseeing trip but we had a fabulous time, it is beautiful and well worth the effort. We hired bikes from Béziers planning in taking the train to Toulouse but if course there was a rail strike in so the hire company delivered them for us. We stayed in hotels on the way and ate some great food. Highly recommended. Looking forward to other episodes

Great article. I sailed on the canal du Midi for a day..It was fantastic, and we stopped at the same restaurant you did. Et on mange bien le long du canal!