Lessons On Patrimoine From Chartres

France has created a vast machine to preserve its cultural and architectural heritage.

During the winter holidays, we escaped the concrete confines of Parisian suburbia for a day trip to the surrounding countryside that eventually led us to Chartres. Just over an hour southwest of the capital, this city of 40,000 people is best-known for its Cathédrale Notre-Dame.

Sometimes it feels like France has as many Notre Dame cathedrals as New York does Starbucks. But a few stand out, and Chartres’ cathedral is definitely one of them.

Despite this being vacation season, we easily found parking in the old city center and walked a short distance through the medieval streets to reach Notre Dame. The city has a reputation for being a haven for artists and creatives, and the majestic Gothic cathedral is a symbolic beacon of that community.

One thing that sets this Notre Dame apart is that it has remained largely intact through France’s various historical upheavals and the fierce northern environs. What was built between 1193 and 1250 is, for the most part, what one sees today. Typically when we visit such an edifice, it comes with a story about being ravaged by fire or being partially disassembled by revolutionary militias, or just being stripped of its riches for yucks. Indeed, the previous Romanesque church that once stood on the same site was destroyed in a fire.

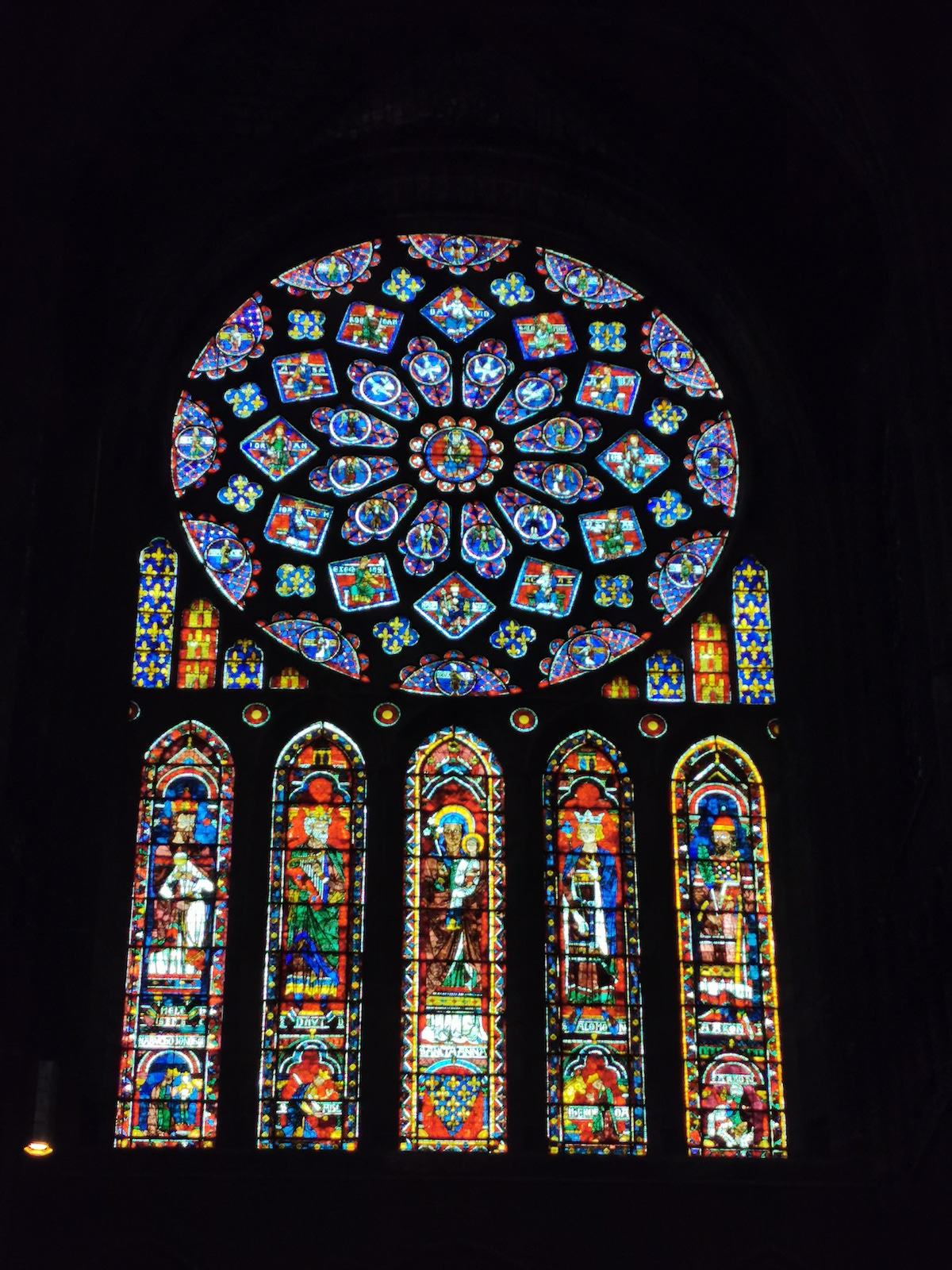

But the other renowned feature of Chartres’ Notre Dame is its stained glass windows, most of which are also originals. Financed by local businessmen at the time, many include a blue tint known as the bleu de Chartres that artisans have been unable to replicate. The legacy of these windows is profound and even inspired the creation of France’s only museum and workshop dedicated to teaching the art of stained glass windows.

Saving France’s Patrimoine

One of the things that has fascinated me since arriving in France is the vast amount of resources that are dedicated to preserving and restoring the nation’s cultural heritage or patrimoine. The concept of patrimoine can include natural landscape, language, and music. But here I’m thinking mainly of the physical patrimoine: cathedrals, old city centers, and the array of architectural wonders.

I’ve tried to calculate just how much is spent on such projects, but the interlocking gears of funding mechanisms are too complex. There are national, regional, and local governments. Then there are non-profits, crowdfunding campaigns, and even a national lottery to raise money.

Stéphane Bern, an elven-looking journalist, has become France’s Mr. Patrimoine (in addition to his work hosting the local Eurovision broadcast each year). His ongoing TV series Secrets d'histoire tells stories about little-known bits of history. He also hosts the annual TV extravaganza le village préféré des Français, a contest where little towns across the country compete to be named France’s favorite village. And after being named a kind of patrimoine ambassador by President Emmanuel Macron, Bern launched that national lottery to raise money for saving its wonders.

While Bern’s celebrity is just one example of how patrimoine is a popular cultural obsession here, it is also an economic and political imperative. Keeping all these sites in tip-top condition is an essential investment in drawing tourists to famous and obscure locations. Dispensing funds for such projects is the surest way to gain favor with local voters.

But that may sound more cynical than intended because really I find it marvelous. And while visiting the Chartres Notre Dame, we got a glimpse of just how intensive and dedicated this work is.

One of the other centerpieces of the cathedral is the “choir,” a semi-circular ring of engravings, façades, and statues that stretch 20 feet high and 325 feet around.

Work to clean and restore this masterpiece is one of the 3 big restoration projects underway. It began in 2015, and will likely not be finished until 2022. There are 40 sections of the choir and so far 27 of them have been cleaned. Over the years, smoke from candles along with visitors’ greasy paws had blackened the white stone,

Here is a sort of before-and-after picture:

For this cleaning, specialized artisans cover each inch of the choir with a special latex material and then peel it away to remove the soot and dust. This is a 4-minute documentary explaining the elaborate process (subtitles should be set to English).

Part of the costs were covered by a non-profit called the Friends of the Cathedral, which raised €1.7 million. Another €730,000 million is yet to be raised for the project, which is also receiving some government support. Other groups, such as the American Friends of Chartres have been raising money to restore some of the stained glass windows.

Meanwhile, the Regional Conservation of Historic Monuments has budgeted €21 million for a more general interior renovation that began in 2007 and will continue until 2024. And a third project is dedicated to cleaning and restoring a section known as La chapelle Saint-Piat. Now that the outside of this chapel has been restored, work in the interior, which has been closed for almost 2 decades, is just beginning.

I know that the United States does its share of historic preservation. But more often, I feel that there is more of a willingness to discard the old in favor of the new. Small towns whither away and become ghost towns. Historical memories are short.

For France, this patrimoine-mania is an example of how deeply history resonates in daily life. There may be an economic imperative, but this desire to preserve is clearly a part of the cultural DNA, a closely-held value that goes beyond financial considerations.

As strangers in this land getting to experience all these cultural treasures, we remain ever grateful for that massive patrimoine machine.