Once Upon A Time In France: The Election Freakout Edition

The ongoing misreading of Le Pen and her supporters could lead to her victory in Round 2 on April 24.

The results of the first round of voting are (almost) complete and as widely expected, President Emmanuel Macron will face off against Marine Le Pen on April 24 in the second round of voting in a rematch of 2017.

The night took on some unexpected suspense after all the candidates had made their concession speeches. The initial results announced at 8 p.m. are just an estimation, though historically highly accurate. But towards midnight, those estimates were revised showing Melenchon a mere .8% behind Le Pen, a big drop from the initial 4.2% gap when he conceded. In the end, he fell about 422,000 votes short, or 1.2%.

There is likely to be a lot of finger-pointing at the Green Party which ran a candidate, Jadot, who never had a chance of winning and whose votes might have made the difference to put Melenchon in round 2. But if one or two other left candidates had dropped out, it might have put Melenchon over the top.

The other results offered some mild shockers. Socialist Party candidate Anne Hidalgo got less than 2% of the vote and Les Republicains candidate Valérie Pécresse was under 5%. These were the 2 dominant national parties of post-WWII France and they have essentially been annihilated. In both cases, I think there was some strategic shift of votes to other candidates as it became clear they had no chance.

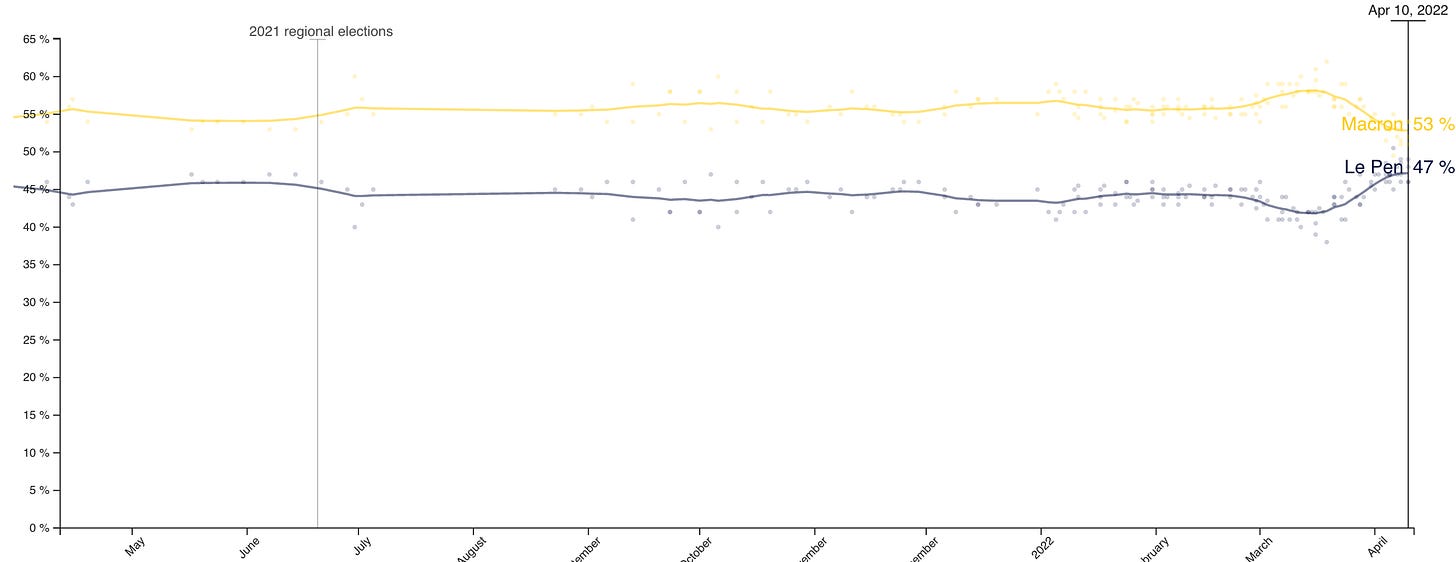

But the real stomach-churning news is that Le Pen seems to have a legitimate shot at winning and that prospect has left a healthy chunk of the French population stupefied and the world in a mild state of shock. Initial flash polls Sunday night showed Macron ahead just 51-49 against Le Pen. Politico’s Poll of Polls shows the race at 53-47, despite the recent tightening, stable overall. Five years ago, Macron won by almost 30 points.

This election included an underappreciated historic milestone. It was the first time I voted in an election since I became a French citizen one year ago. However, it seems France is determined to make this an anxiety-riddled experience that comes down to casting a vote in the hopes of avoiding the victory of a right-wing candidate who would likely prefer that people like me not be in the country at all, or at least be stripped of most of our benefits.

That this is going to be nailbiter is itself an unexpected twist. Just a few weeks ago, there wasn’t much drama surrounding this campaign. Macron was far ahead in the polls and looked like he would cruise to victory in the second round on April 24 no matter which candidate he faced. His statesmanship in the Ukraine crisis seemed to have given him a boost in a race he was already favored to win.

But in the last 10 days, the polls tightened. Le Pen continued to gather steam on almost a daily basis.

There are a few important caveats. As FiveThirtyEight notes, French polling takes a particular approach regarding undecided and voting intentions. And last year in regional elections across the country, polls overstated support for conservative candidates aligned with Le Pen. Also, in the 2017 election, French polling underestimated the size of Macron’s victory in the 2nd round against Le Pen by 10%.

That said, it’s going to be two weeks of misery awaiting the outcome. As an American living in France, it feels like it is always election season. And because the conservative side has become more and more extreme, it feels like each election is existential, like the very nature of the country is at stake. When the French presidential election ends, there will then be elections to see who controls the National Assembly. And once that ends, I can go back to incessantly worrying about the November mid-terms in the U.S.

Honestly, it’s enough to make me support a restoration of the monarchy just to have a few years without elections.

Macron’s Slide

Macron’s 5 years as president have been marked by extraordinary events. For more than a year and a half, the Yellow Vest protestors dominated the political landscape. His attempts to address at least some of their concerns didn’t really change many minds about him being an out-of-touch elitist banker in his Paris palace.

Likewise, a surge of Green Party success in local elections two years ago affirmed just how disappointed many remained over his lack of action to address climate change, despite big talk in international forums.

More recently, he has been getting dragged over accusations that the government used the services of international consultants such as McKinsey that did not pay taxes in France. To the degree that Macron has appeared on TV to discuss his campaign, he mostly seems to be on the defensive over these allegations. Meanwhile, a Paris court has opened a formal investigation after a Senate report about the influence of consultants.

Then there is the general pandemic fatigue. Every candidate has blasted Macron for his handling of the crisis, though I have not read any coherent explanations of what they would have done differently. The government ended almost all restrictions just a few weeks ago, which predictably has led to a rise in cases. And that in turn has once again driven home the grim truth that this pandemic will endure. Add in rising energy costs that forced some small towns to suspend municipal services, and the war on the nation’s doorstep, and spirits are not high.

Yet, for all of that, Macron has not gotten the credit for what he has done well. Part of that blames falls on him. As he appeared to be cruising to victory, Macron opted to remain above the fray, declaring his official candidacy at the last minute, skipping any potential debates, and only holding one official large campaign rally. And somewhat inexplicably in this truncated campaign, Macron opted to bring up one of his most controversial proposals to reform France’s retirement system, an idea that provoked a huge backlash before being set aside because of the pandemic.

As a result, nobody has been making a case for his successes, and there is indeed a case to be made.

As the New York Times’ Paul Krugman wrote in January, France’s economy had one of the best performances of the pandemic thanks to Macron’s aggressive financial measures to support businesses and employees. Indeed, employment in France now stands at 7.4%, down from the double digits Macron inherited, and that had remained stubbornly high for years. On top of that, the number of jobs being created that provide long-term contracts (CDI) has increased after falling for years. This is perhaps even more remarkable with the pandemic thrown in the middle.

In other measures, France’s economy continues to overperform. As Phillip Inman recently wrote in The Guardian, the 4.5% inflation in France may be historically high, but it is far better than the “UK’s 6.2%, Germany’s 7.3%, Spain’s 9.8% and 11.9% in the Netherlands.” Macron’s move to limit energy price hikes by energy providers has kept a tighter lid on the inflation rate here.

And as someone who writes a fair bit about France’s tech scene, I would note that funding for startups and hiring by these companies has exploded over the past five years.

For all of this, Macron’s problems may be just as much about style as it is about substance. He has never managed to shake his veneer as an aloof technocrat. He offered some mildly stirring calls to arms during the pandemic, but on a human level, a lot of people in France simply do not believe he understands their problems or cares about them.

My early adulthood was marked by the campaign of Bill Clinton, who delivered a thunderbolt of a line during a 1992 debate when he looked at a voter and said, “I feel your pain.” For all of Clinton’s faults (and they are numerous), what carried him forward was remarkable displays of empathy.

Macron, in contrast, seems to lack the empathy gene. As Economy Minister, he famously told a striking worker to his face that the best way to be able to afford a suit like the one he was wearing was to work. As president, Macron’s first term included an awkward encounter with a young man who was unemployed. When the man recounted his difficulties, Macron told him that all he had to do was cross the street and look harder because businesses were hiring.

The French president is a self-professed fan of Obama. But he could use a bit more of Clinton’s “I feel your pain” mojo to humanize himself.

How Do You Solve A Problem Like Marine Le Pen?

With Le Pen closing the gap, Macron and his supporters launched a panic campaign that mainly involves trying to re-demonize Le Pen for her ties to Russian mobster-president Vladimir Putin. On Sunday night, TV pundits talked of the strategy of “diabolisation.” Le Pen has received substantial financial support from Russia over the years and has been quite open in her support for Putin, including during the Ukraine crisis.

In the eyes of Macron supporters and liberals, these ties should a priori disqualify Le Pen from any serious consideration as a candidate. Anyone who is willing to support such a person as Le Pen is, in turn, contemptible.

Even most vanquished opponents rallied to Macron’s side (while emphasizing how horrible he is) by saying the nation needed to unite to block Le Pen and the horrors of the extreme right. Melenchon was a notable exception, as he was in 2017, in saying his followers should not give a single vote to Le Pen but refusing to outright declare that he would vote for Macron.

I would happen to agree with that overarching sentiment regarding Le Pen. However, it’s also clear that much of the French electorate is willing to overlook these Russian ties for reasons that are more complicated than the knee-jerk analysis that claims “the French are willing to support fascists.” I’ll come back to that later.

Beyond Russia, one of the biggest themes of this election is the expression of shock that the French electorate has drifted so far to the right. This is explained by tallying up the respective polls which show a clear majority favoring candidates from the soft center-right (Macron) to the far-right (Zemmour). Le Pen continues to be labeled “far-right” or “extreme-right.” Based on vote totals Sunday, Macron (center-right) had 28.6%, the hard-right had 37.7%, and the left just 30.4%.

Still, the problem with much of the reporting around these trends in recent months is that they tend toward lazy horse-race reporting that focuses on identity, labels, and palace intrigue. The New York Times has been particularly obsessed with this trend and offers a couple of prime examples.

This story by Elisabeth Zerofsky for the New York Times Magazine, spends a lot of time on the decision by Le Pen’s niece (perhaps the biggest loser of this campaign?) to defect to the campaign of Eric Zemmour, along with the question of immigration, and some other cultural issues. But it only makes a glancing reference to Le Pen’s economic agenda, saying:

“Le Pen, who is 53, has positioned herself as an economic populist, seeking to attract working-class voters from across the political spectrum, caring little if they identify as right or left.”

Times’ reporters Norimitsu Onishi and Constant Méheut offered a similar diagnosis:

“…virtually the entire French campaign has been fought on the right and far right, whose candidates dominate the polls and whose themes and talking points — issues of national identity, immigration and Islam — have dominated the political debate. The far right has even become the champion of pocketbook issues, traditionally the left’s turf.”

But these stories fall into the same trap on which they are reporting: The idea that the election is solely about cultural and immigration issues, and that the rise of a right-wing media machine has effectively manipulated the populace and duped them into supporting candidates like Le Pen. Certainly, culture and identity are playing a bigger role in French politics, and the right-wing media ecosystem has blossomed here. But much of this reporting treats the French like mindless fools who are being suckered into following one candidate or another.

I think there is a more fundamental dynamic here, and to understand what that is it helps to actually look at Le Pen’s economic agenda.

Liberalism vs Protectionism

While Le Pen is often compared to Trump, there are some critical differences. Unlike Trump, she is a lifetime politician who has amassed fairly detailed policy proposals. While the media brushes these off dismissively as “economic populism,” her ideas here are well within the French mainstream.

For instance, her big idea is to create a Fonds Souverain Français. Citizens could invest in this fund and get at least 2% annual returns. The money would be used to invest in a wide range of projects, from re-acquiring the management of some French highways from private companies (and lower tolls) to scientific research in a variety of fields to enhancing climate change programs. The idea is to create a kind of patriotic investment scheme.

Beyond that, Le Pen wants to ensure any foreign economic competitors in France abide by local labor and tax rules; ensure that government purchases favor French companies; build 100,000 social housing units for low-income families and students; adapt the retirement age from 62 to 60 for some categories of workers (Macron wants to raise it to 65); improve health are and teacher salaries; stop hospital closings and address the “medical deserts” in rural areas; improve price support for farmers and plans that would require school cafeterias to buy local; increase retirement plans; provide interest-free loans for young families; cut energy taxes; eliminate taxes for entrepreneurs under 30 so they stay in France; and increase taxes on financial wealth.

Oh, and Le Pen is big on animal rights. She’s been ridiculed for using her cats to soften her image. But in terms of policy, she wants to give animals constitutional rights and protections and hold a national referendum to enshrine further protections. Macron, in contrast, has spent 5 years publicly courting the conservative hunting lobby.

We can dispute the economic wisdom of her various policies. But one thing you can’t call them is “extreme.” While they don’t align perfectly with those of Mélenchon, they are very similar in spirit. Putting “France First”, increasing social spending, improving retirement and health care support, and rebuilding the French economy from within rather than relying on expanded free trade and work reforms that give employers a freer hand.

When people see polls that suggest that Mélenchon voters might back Le Pen in the 2nd round, they become indignant. It is a betrayal, they sniff, a sign that two political extremes are made up of dangerous fellow travelers who just want to back extremism for its own sake. But this is a dangerous dismissal of the motivation of these voters.

Consider this analysis by the Jean Jaures Foundation. The left-leaning think tank combed through Le Pen’s agenda and noted that while her public image has softened, her policies overall remained dangerously extreme in terms of immigration, crime, and social policy. But the exception was her economic plans. The analysis noted that “FN moved in the 2000s from neoliberalism to ‘social-populism’, from the anti-tax party to a 'tax on financial wealth’ and measures in favor of purchasing power.” The report adds: “The far-right party ‘has very strongly amended its position, going from a very clearly anti-redistribution line in the 2000s to an approach rather in favor of redistributive mechanisms at the present time.’”

Indeed, this kind of economic protection is not only not “extreme,” it is arguably supported by the majority of French. That was the case in the first round of 2017 when protectionist candidates received a majority of votes. And it was certainly the case Sunday night in the first round. Melenchon and Le Pen won at least 45% of the vote, and with the other left candidates, the “protectionism” vote was well over 50%.

In this regard, it is the economic liberalism championed by Macron that remains a minority idea in France.

This, then, is perhaps the fundamental failing of Macron’s first term. Through his ups and downs, successes and failures, he has smashed the traditional political parties but he has not built majority support for his drive for reform and liberalization of the economy. Even if some data suggest its merits, Macron has not sold the nation on this concept.

Put yourself in the shoes of a small town or rural resident who has struggled to find work and can’t make ends meet each month. You are being asked to choose in the 2nd round between five more years of liberalization, or a candidate whose agenda offers a break from the relentless globalization of recent decades. But are you concerned enough by events in Ukraine and a candidate’s ties to Russia to vote against what you consider to be your economic interests?

That is a difficult choice. Some of those voters will be motivated by fears of immigration and cultural/identity issues. But many more will also be focused on the economy.

None of this should be viewed as an apology for Le Pen’s odious views on Islam and immigration. I am indeed horrified by the notion of her becoming president. But trying to place her along a simplistic spectrum of left-right and extreme-moderate, obscures her appeal and the reasons many voters might be attracted to her.

In failing to engage with those real motivations and fears, by simply trying to characterize and demonize Le Pen in the hopes that will be enough, Macron’s campaign is in danger of alienating the voters it needs by effectively calling them racists and fascists. And just as critically, it may not be a persuasive message for Melenchon voters who are horrified by the prospect of five more years of liberalization.

As was the case in 2017, it really is a shame that Melenchon did not advance to the 2nd round. France could have the robust debate it needs to have around its economic future and climate change policy. Instead, we will have 2 weeks of apocalyptic warnings about the need to stop the fascists.

That worked in 2017, but it may not be enough in 2022. Such an unwillingness to engage in these debates against Le Pen could elevate a candidate whose presidency would have grave consequences for France and the EU just at a moment when it seemed the continent was more united than it had been in decades.

PS: One nuance to this liberalization vs protectionism debate is what Macron actually did over the past 5 years. With first the Yellow Vests, and then the pandemic, he turned to big government spending programs and social support, as noted above. The France Relance 2020 program envisions spending €30 billion on a wide range of investments to reboot France’s economy, and that’s just a piece of it. That doesn’t include billions of euros for various tech-related programs and training. The result is an increase in France’s debt which likely altered Le Pen’s plans: She was counting on big deficit spending in 2017 to boost consumer purchases, but because one has to be reflexively anti-Marcon, she has gone to pains to demonstrate that her plans do not increase the deficit. In an editorial supporting Macron overall, The Economist chided him for being “too eager to reach for the levers of state control, whether capping electricity prices or meddling in the management of hypermarkets.” In other words, his first term was really a mix of liberalization and protectionism, but politics rarely allow for such subtle distinctions.