The Fire That Saved Notre Dame

The remarkable glow-up officially unveiled last weekend would have been unimaginable 6 years ago when boosters were begging for restoration funds.

Even amid a year of political turmoil, France has experienced two remarkable moments of national unity.

The first was the Summer Olympics Games. What many assumed would be a disaster instead turned out to be a glorious triumph.

The second came last weekend when the nation temporarily hit pause on its political squabbling to rejoice in the re-opening of the Cathedral of Notre Dame. About 5.5 years after a fire ravaged the church and captured global attention, the church celebrated with a grand unveiling that drew heads of state from around the world.

Shortly after the fire in April 2019, President Emmanuel Macron vowed that the Cathedral would be restored within 5 years — an aggressive schedule that elicited widespread skepticism. And yet, there was the president basking in the re-opening last weekend (though the Olympics and Notre Dame haven’t boosted his reputation with voters much).

He even used the occassional to stage a diplomatic coup by getting President-elect Donald Trump and Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelensky in the same room.

The sublime state of Notre Dame today would have seemed almost unimaginable on the day of the fire.

But what is also mostly forgotten is that seeing Notre Dame in 2024 in this condition would have seemed every bit as unimaginable the day before the fire.

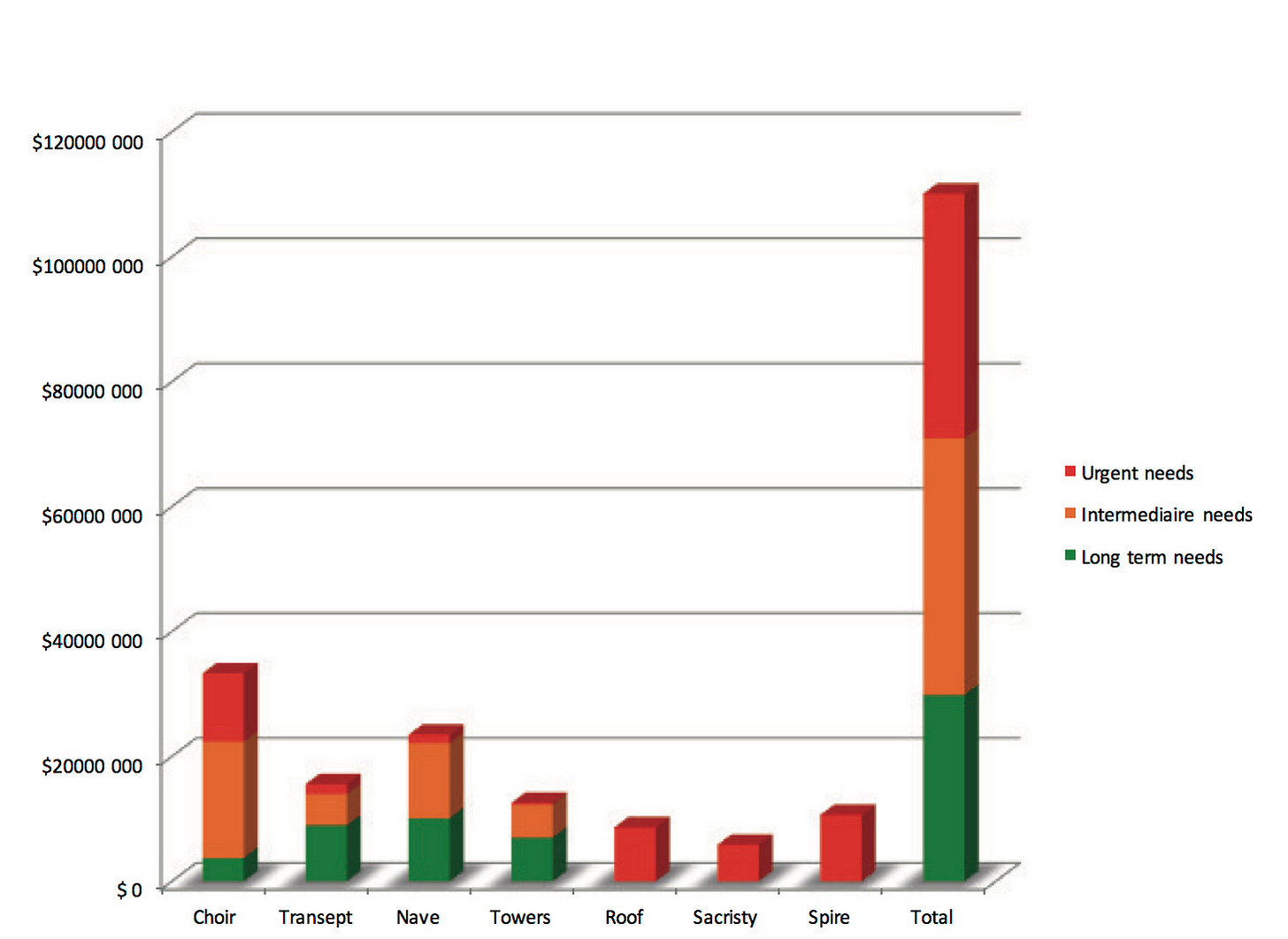

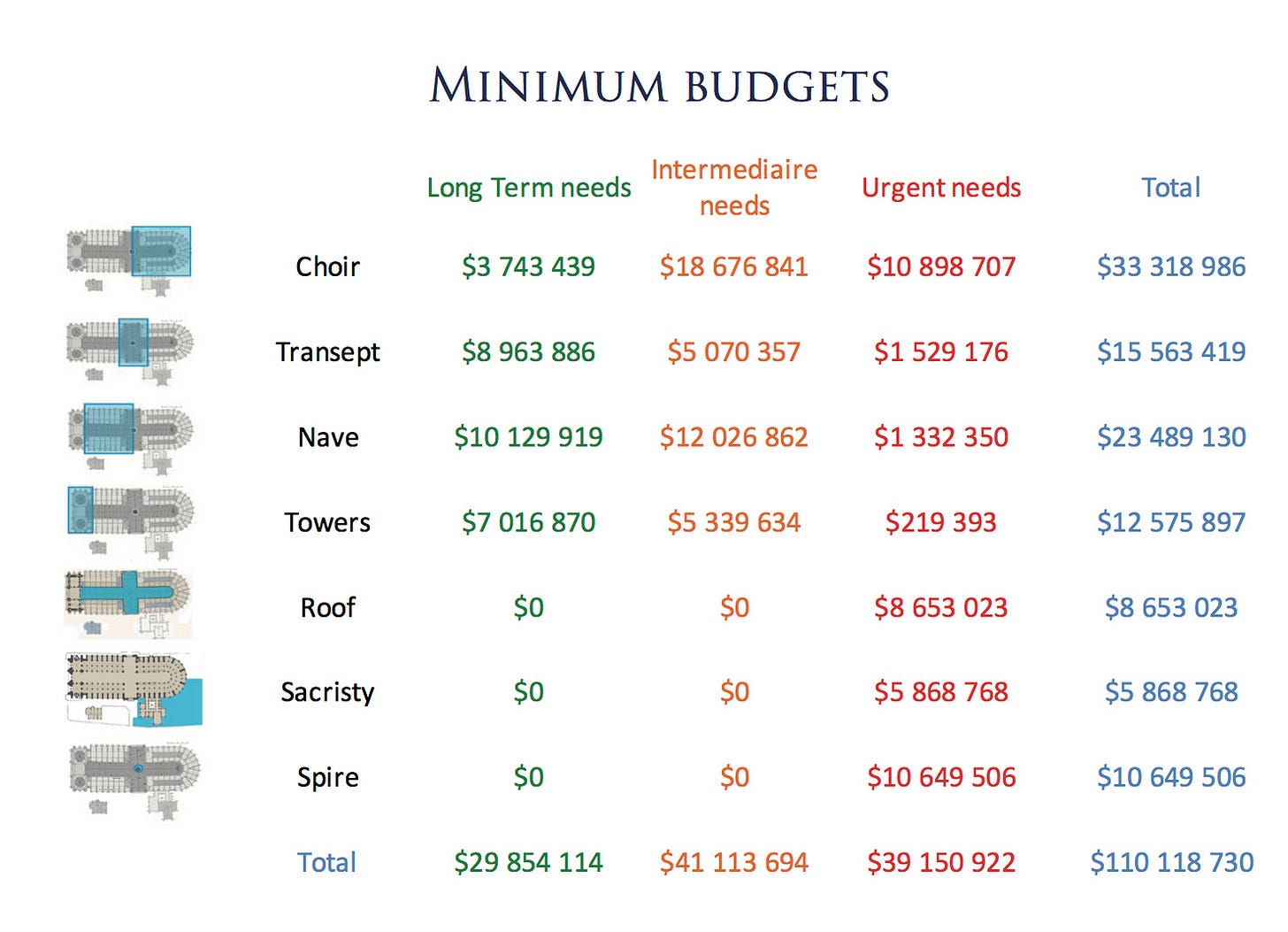

In the preceding years, the various groups — religious and non-profit — that support the building had been sounding an alarm: The Gothic wonder was crumbling and in desperate need of €110 million worth of repairs. These pleas had little impact as the groups pushed to scrape together the minimum to prevent what they promised would be a catastrophe.

Consider this description in 2017 from the Friends of Notre Dame website, a group created to find international donors to fund renovations:

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame is in desperate need of conservation. No part of the building has not been subject to decay and there are several areas of concern Although the recently restored western façade is radiant, the same cannot be said of the rest of the building…Maintenance work has been carried out, but it has not been sufficient to stop the spread of conservation problems; there is no part of the building untouched by the irreparable loss of sculptural and decorative elements, let alone the alarming deterioration of structural elements….The poor state of the stonework is particularly problematic with respect to the flying buttresses. Should even one of these structural pylons fail because of the damaged stonework, the consequences would be disastrous...The famous gargoyles of Notre-Dame, all carved in the nineteenth century, and which perform an essential role of projecting rainwater away from the building, have in many places been replaced with unsightly PVC tubes because the stonework was too corroded (and thus dangerous) to leave in place.”

Given that they were in fundraising mode, there was no doubt some hyperbole. Still, the images on their website and the descriptions by third-party observers made it hard to deny that the church was facing a severe crisis.

To attract international donors, the group launched a press blitz in 2017. When The New York Times visited that year, the outlook seemed grim:

Broken gargoyles and fallen balustrades replaced by plastic pipes and wooden planks. Flying buttresses darkened by pollution and eroded by rainwater. Pinnacles propped up by beams and held together with straps.

Little of that deterioration is immediately visible to the millions of awe-struck tourists who visit the Cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris every year, many of them too busy admiring the intricately sculpted front to notice the wear and tear.

But on a recent afternoon, André Finot, the cathedral’s spokesman, pointed out the decay. One patch of limestone crumbled at a finger’s touch.

“Everywhere the stone is eroded, and the more the wind blows, the more all of these little pieces keep falling,” said Mr. Finot, gingerly stepping over fallen chunks of stone on the cathedral’s rooftop walkway. “It’s spinning out of control everywhere.”

That same year, Time Magazine described the situation as bleak:

One blazing hot day in early July, a staff member unlocked an old door off the choir and led TIME up a stone spiral staircase and out onto the roof, high above the crowds. Here, the site seemed not spiritually uplifting but distressing. Chunks of limestone lay on the ground, having fallen from the upper part of the chevet, or the eastern end of the Gothic church. One small piece had a clean slice down one side, showing how recently it had fallen. Two sections of a wall were missing, propped up with wood. And the features of Notre Dame’s famous gargoyles looked as worn away as the face of Voldemort. “They are like ice cream in the sun, melting,” says Michel Picaud, head of the nonprofit Friends of Notre Dame de Paris, looking up at them

What is more, some fear the problem is getting worse. “The damage can only accelerate,” says Andrew Tallon, an associate professor of art at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., and an expert on Gothic architecture. Having carefully studied the damage, he says the restoration work is urgent. If the cathedral is left alone, its structural integrity could be at risk. “The flying buttresses, if they are not in place, the choir could come down,” he says. “The more you wait, the more you need to take down and replace.”

The church was not fully aware of the extent of the problem, say those at Notre Dame. Until a few years ago, the government effectively made the private areas off-limits. “There used to be about 200 old keys, so it was very, very difficult,” says André Finot, a spokesman for Notre Dame. Eventually, the government standardized the keys and allowed its tenants to climb the hidden stone staircases and access the upper levels. “We were shocked when we got up there,” Finot says.

The non-profit offered a detailed budget regarding what it believed would take to save Notre Dame (forget restoring it to a pristine state):

Part of the problem was the fuzziness about who was responsible for the repairs. The government owns the building and lets the church use it for free. However, it was technically up to the church to maintain it, though the state still chipped in. The French Ministry of Culture had been providing €2 million annually and had agreed to double that in view of the mounting problems. But it wouldn’t come close to funding the $110m needed over the next decade.

As Time reported, the government wasn’t persuaded of the urgency:

This year, authorities budgeted an extra €6 million ($6.84 million) to restore the spire. Water damage to the spire’s covering is threatening the wood-timber roof, which the medieval craftsmen built using 5,000 oak trees. The restoration will begin in the fall. But a Ministry of Culture official says Notre Dame should not expect regular help of this kind. To the government, the cathedral is just one of many old buildings in need of care. “France has thousands of monuments,” says the official, who was not authorized to speak to the media. Among them, Notre Dame is not necessarily the most pressing case. “It will not fall down,” she says.

As tragic as the fire was, it galvanized people around the world in a way that the slow-motion decay never would have.

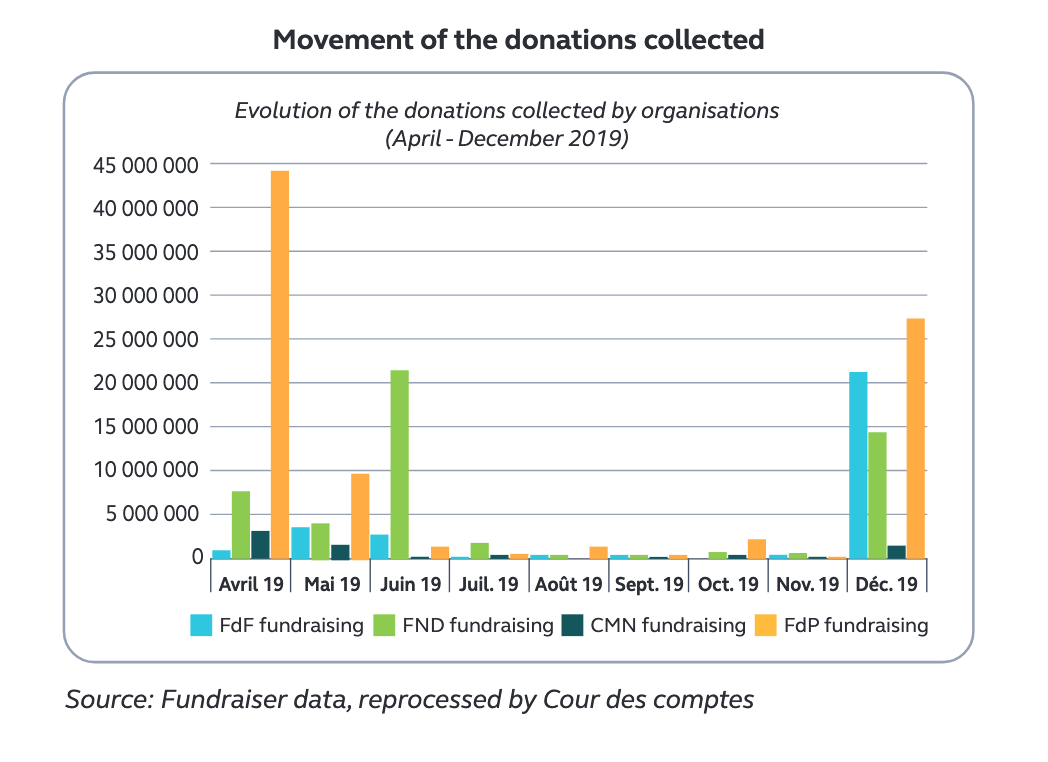

The Cour des comptes, the nation’s auditing agency, described in a 2020 report the $824 million in donations raised for Notre Dame in 2019 after the fire as “unprecedented”:

The national fundraising drive announced by the French President the evening of the fire, and organised by the law of 29 July 2019, enabled a considerable number of spontaneous donations in the very first days. This fundraising dynamic was manifested again at the end of the year, in particular thanks to the use of diversified digital media and online payment. This exceptional outpouring of generosity from individual donors was supplemented by sponsorship contributions from companies, and these huge amounts appear to be completely unprecedented: as of 31 December 2019, 331,762 individuals had made an average donation of €196.50 and 6,012 companies provided average sponsorship €17,304.”

No more passing the beggar’s bowl.

Of course, this is not intended to recommend torching historic sites as a fundraising strategy. As we learned later, Notre Dame came perilously close to collapsing. Had that happened, the nation would have faced an unthinkable price tag for rebuilding Notre Dame.

Still, the funding problems that plagued Notre Dame before the fire are still the ones facing thousands of historic sites across France, particularly churches that are managed by local towns and cities, or private sites that are less heralded, but still have been granted official historic status. Each site is scrambling to cobble together money from a patchwork of sources —governments, non-profits, individual donors, and religious institutions. France has even launched a Patrimoine lottery to raise funds, this also is just a few crumbs compared to the larger need.

Supporters note that these sites generate enormous cultural and economic value, drawing tourists who support local economies. But that has hardly made for a compelling argument to rally the cash needed. In the wake of Notre Dame, the French government adopted a €220m program to provide extra cash for 87 cathedrals to improve fire security and perform some maintenance. Yet that was considered a mere drop in the bucket.

The real cost of restoring France’s Patrimoine is so large and complex and spread across so many actors that no one can even calculate the number.

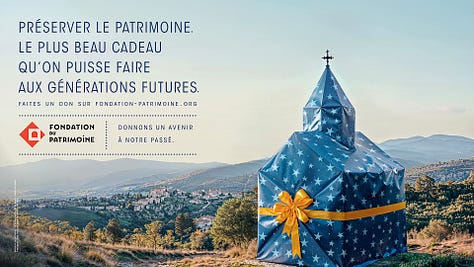

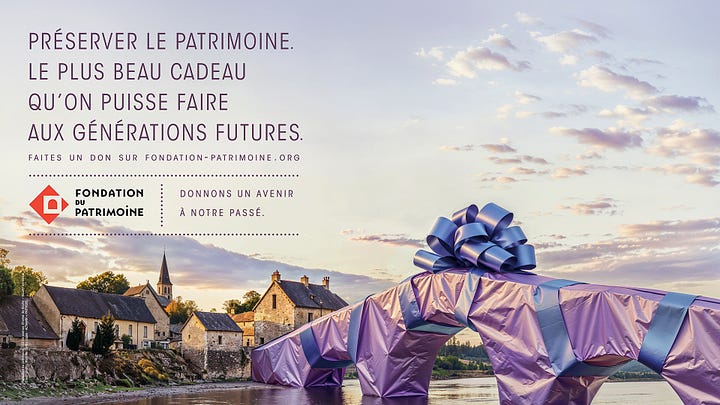

With the government headed toward some kind of austerity budget, there’s unlikely to be much extra help coming from politicians. Meanwhile, the Fondation du Patrimoine has just launched a national marketing campaign with the slogan, “Donnons un avenir à notre passé.” (Let’s give a future to our past) The goal is to leverage the enthusiasm surrounding Notre Dame’s re-birth.

Hopefully, Notre Dame will inspire donors. But if history is a guide, it’s a challenge to mobilize people to fight a slow-motion crisis they often can’t see or feel. Even in a nation where the past is ever-present.

Chris O’Brien

Paris, France