These Chefs Want To Make Breakfast A Thing In France. Will The French Bite?

The morning meal gets little love here. An association of chefs and hotel operators hopes its annual breakfast competition will get people to wake up to its potential.

The gulf that lies between the French and American attitudes toward the first meal of the day is right there in the words we use.

In America, we “break” our “fast” in the morning, typically with a solid meal. In France, this label is reserved for lunch: déjeuner. The word “jeun” refers to an empty stomach. When one goes to have bloodwork done at a lab in the morning in France, we are told to come à jeun, not having eaten anything.

When confronted with the existence of something new, the French turn themselves in pretzels trying to avoid inventing another world to add to the language’s vocabulary. And so, as the nation came around belatedly and grudgingly to acknowledging the existence of a meal-ish before lunch, they dubbed it petit déjeuner, the perfect phrase to certify its second-class status.

For Americans raised on the BREAKFAST IS THE MOST IMPORTANT MEAL OF THE DAY mantra, the French breakfast is woefully disappointing and unsatisfying. There may be no bigger reality gap than the one that exists between an American’s romantic notion of a French breakfast and the sad reality of this morning meal.

In the mind of said American, a sumptuous croissant lies at the heart of the French petit déjeuner. Warm, steaming, buttery, just out of the oven, this folded pastry wonder seems to fall apart at the touch and melts instantaneously upon touching your tongue. A nice espresso then follows to momentarily electrify your mouth, before filling the belly with contentment. This mythology is perpetuated by countless Instagrammers, sitting on a hotel terrace with their feet languorously dangling on the rail and next to a dazzling plate of pastries and gazing at the Eiffel Tower in the distance.

The truth is that French breakfast typically consists of a croissant that has been sitting in a large box at the boulangerie for hours before being fished out and stuffed in a paper sack. The slight staleness can’t quite be warmed away by the oven, which only seems to emphasize its sadness. One could write an entire lament about the pathetic state of French coffee but suffice it to say that this is not Italy, and Nespresso has somehow tragically captured this market.

When people ask me what food I miss from the U.S., I simply say: breakfast.

So, when I first learned about a contest called Trophée du Petit Déjeuner, my heart soared. I discovered this competition, alas, just before the pandemic turned our lives upside down in March 2020. And so, after starting to report this, I put the topic aside. But late last year when I heard about the latest edition – now dubbed Meilleur Petit Déjeuner & Brunch de France – I decided to strike while the pancake griddle was still hot.

The annual event is organized by Tables & Auberges, a national association of chefs, hotel owners, and local food producers. Broadly speaking, the goal is to celebrate this nation’s best breakfasts to rescue this orphaned morning meal and give it the gastronomic respect it deserves. Awards are given in 6 categories (see the winners here). Participants are supposed to emphasize local and seasonal products, sustainability, and culinary savoir-faire.

The contest organizers are motivated by a mix of economics and nutrition, according to Stéphanie Martinez, a Tables & Auberges spokesperson. Given that so many members are hotel or B&B owners, they wanted to emphasize how critical breakfast can be for guest satisfaction. Even better: A more sophisticated morning meal gives local producers another place to sell their products.

“The reason for the competition was to showcase the morning meal,” she said. “As it happens, the question of breakfast arose above all in relation to hotels because in many hotels, breakfast is not necessarily promoted as it should be. But breakfast is the last thing guests remember when they leave the establishment. You're more likely to return to a hotel because you've eaten well and it's the last memory you have before leaving.”

Then there is the broader question of elevating the prestige of the meal and encouraging the nation, in general, to take it more seriously. As Tables & Auberges noted in its description of the contest:

“86% of French people consider that it is important to start the day with a good breakfast, but in reality, things are different. With around a quarter of an hour devoted to this meal we cannot afford too much morning fantasy. According to the national nutrition and health plan, breakfast is a meal in its own right and must represent between 20 and 25% of energy intake over the entire day. Today, only 19% of adults and 30% of children eat a full breakfast consisting of a grain food, a dairy product, a fruit, and a hot or cold drink.”

In France, where good eating is at the heart of the national identity, the effort to rally the country around this initiative has become serious enough that the competition is co-sponsored by France’s ministers of agriculture, finance, and economy. Tables & Auberges has just opened the call for nominees for its 7th annual competition, with an official theme around dairy and cheese products.

Make Breakfast Great Again

In talking to researchers and historians about French and American breakfast habits, I realized that I bring my cultural weight to this topic.

Growing up in the U.S., the whole MOST IMPORTANT MEAL OF THE DAY ethos is drilled into our heads. I remember in the 1970s watching Saturday morning cartoons and being treated to the public service announcement: “The Breakfast Droop” by the National PTA.

“When your mornings lag and you sort of sag and you can't keep up with the group/and you're not in tune ‘till the afternoon, then you got the no breakfast droop./Now there is a way you can start the day so the first part, good is the last make more of the deal of the morning meal./ In other words, chum, break the fast./ So, eat breakfast, don't pass it up.”

This is mostly marketing hokum. In the 1940s, cereal makers in the U.S. started an advertising campaign (“Eat a Good Breakfast—Do a Better Job”) that worked wonders. Over time, studies emerged claiming to confirm that breakfast promoted good health. As it turns out, most of these were flawed and funded by the food industry. There is even an institute called The International Breakfast Research Initiative (financed by the cereal industry).

The French are much more capable of sniffing out the hints of capitalism behind something and resisting its seductive lure. In this sense, a robust breakfast can also be seen as an Anglo thing pushed by large companies, yet another cultural invader to be repelled to protect the essence of French culture. (As we see in other areas, resistance is fading.)

Yet, despite knowing that I have been a lifelong victim of Big Breakfast, the stomach wants what the stomach wants.

When traveling in France, we have often timidly inquired at various lodgings whether it might also be possible to have an egg or cheese, or just really any protein-containing substance with our petit déjeuner. This may typically be met with a raised eyebrow and a look that silently says, “You Americans and your breakfast.” During a visit to my doctor after we had been in France for a couple of years, we were reviewing my eating habits when she stopped, somewhat shocked, to make sure she had heard me correctly: “You have eggs at breakfast…every day? Surely that’s too much protein.”

In some cases, we stumble across the classic British breakfast, a feast that seems even more disappointing for having gotten one’s hopes up only to find a plate swimming in baked bean sauce as it drowns fried eggs that are holding on for dear life to two inexplicably grilled tomatoes as two brown logs pretending to be sausages bobbing along.

Many are the conferences I’ve attended that promised breakfast which turned out to be trays of unsatisfying croissants, and sometimes chocolatines, or what the barbarians in the North of France refer to as pain au chocolat.

Beyond the lack of tastebud satisfaction, it simply isn’t filling. I’m hungry an hour later and usually am scrounging for snacks. The French are famously not snackers whereas Americans are relentless grazers. The French hold tight until 12:30 p.m. and then take a nice long lunch. It’s impossibly civilized in a world that wants us to constantly be rushing.

Even trying to make our own Real Full American Breakfast at home can be difficult. Bacon as we know it is scarce. If you order bacon at the butcher’s shop, you more likely get something closer to the dreaded Canadian “bacon” with a long stringy strip along the edge that is inedible. Closer to real bacon are lardons which are often sold in cube form and can help make a delicious quiche. Our saving grace in this regard for many years was the Marks & Spencer in the Paris Montparnasse train station which sold frozen bacon such as would be recognizable to the American palette. Alas, Brexit forced Marks & Spencer to abandon the French market.

The Breakfast Trophy

To learn about the breakfast competition, I attended a February 2020 convention in Toulouse for hotel and restaurant owners where the latest edition was being announced. Attendees had to first pass through a demonstration area created by the Tables & Auberges team to spread the word about their breakfast competition. A fruit seller had concocted a dazzling display by sliding assorted berries, melon cubes, and orange slices onto toothpicks and then arranging them on a half-dome as if they were exploding fireworks. The next stand was Latitude Safran, who created a confiture of Safran that is served in gelatinous bubbles. A butcher was slicing dried ham from a pig’s leg for tasting, while a local apple farmer served their apple juice. The obligatory croissants and chocolatines were placed next to the salmon samples.

All the products were made in the Toulouse region, a point of emphasis for Tables & Auberges. Showing off French quality means discovering the best of local producers in a region. This is a way for visitors to truly feel they are experiencing a place by eating regionally produced food. Expanding the breakfast market also potentially creates new opportunities for French farmers who are often struggling these days.

“We call it petit déjeuner du terroir,” Martinez said. “It's really about showcasing the region with regional products.”

While there was agreement among participants in the Tables & Auberges event that breakfast deserves more respect, there didn’t seem to be much agreement on why the French have given it such short shrift. The main answer, repeated by just about everyone I asked, was that there simply wasn’t time in the morning to prepare breakfast. As a parent, I’m certainly sympathetic to the stress during the morning scramble to prepare breakfast for everyone and get the kids out the door to school. Yet we have long awoken early enough to give ourselves time to do so. And this seemed to be the critical difference.

The French are famously not early risers. My wife used to teach a yoga class in Toulouse at 9 a.m. on the weekends. Back in the Bay Area, the culture around hard-core yogis was to get up and practice 6 days a week starting at 6 a.m. So 9 a.m. seemed rather laid-back. But invariably when she would mention that her class was at 9 a.m. on a Saturday, a look of shock would appear on our French friends’ faces, followed by, “That’s so early! Impossible!”

At the restaurant convention, when I suggested that perhaps people get up a bit earlier, this seemed to be the real hurdle. In the ancient human war between eating and sleeping, the French were firmly in the latter’s camp, despite their gastronomic reputation. Magali Buso, who works for the Haute-Garonne department representing local farmers, told me that to expand her breakfast habits, she had to make a major life change. “I now get up a bit earlier each morning,” she conceded.

The 6th edition of the contest, which was not open to the public or press, was held on November 29, 2023, at L’Ecole de Paris des Métiers de la Table (EPMT). The theme: Fruits and raw or cooked seasonal vegetables. The president of the jury was chef Olivier Bellin (Michelin 2 stars), accompanied by Jean Covillault, who had been a competitor on Top Chef Season 14.

The breakfast competitors didn’t face the kind of pressure seen on that show. Still, cooks had a couple of hours to prepare their meals and then present them to the jury. They were judged on the quality and creativity of the food, but also the presentation.

The winners in each category received €2,000 with €1,000 for second place. There are also gifts of coffee makers, artisanal cutlery, cooking equipment, and gift vouchers.

Martinez said the competition is also a chance to celebrate quality, creativity, and local seasonal products over mass-produced fare.

“The events we organize highlight our members’ savoir-faire,” she said. “There should be no serving packaged butter, no more jams in little jars. But to have real butter, real homemade cakes, rice pudding, really homemade things. This way we can enhance the quality of products on the breakfast table.”

A Cultural Moment

A few weeks later after the Toulouse convention in 2020, I invited Nadine Barbottin to join me for breakfast. Barbottin is a chef and food consultant for events via her company Mamscook. We met at La Cour de Consuls, an upscale hotel in the city center, in large part because there were pretty minimal choices for places that would serve an actual breakfast on a weekday. Barbottin ordered Eggs Benedict while I chose a ham and cheese omelet.

She had won a prize for best regional breakfast in the 2019 competition, a meal that included plates of Southern favorites like strips of magret de canard on a toasted bread that had been brushed with tomatoes, slices of black ham over white beans on toast, deviled eggs with anchovies, and an older regional specialty called milla that uses cornflower to create a flan-like cake.

People ask me what my favorite French dish is. For me, the beauty of French meals is the pleasure, knowledge, and appreciation people have for food and the whole experience of sharing a meal. For Barbottin, the history is just as important as the recipe. As we ate, she talked about how breakfast barely existed several centuries ago in France and then became a meal for the elite as they embraced imported goods like tea, coffee, and chocolate. As breakfast gradually made an appearance as the country industrialized in the 19th century, it was still mostly about bread (with coffee in the cities, with soup in the countryside).

“Bread in France is a crazy thing,” she said. “A Frenchman can't eat without bread!”

Whereas the Anglo-Saxon world expanded to eggs and meat, France and much of Europe still leaned on bread and hot drinks. The Brits eventually came to dub this a Continental Breakfast.

Barbottin wants the French to bring the same passion and creativity to the morning meal as they do lunch and dinner. As she put together her menu for the competition, she drew on forgotten dishes of her childhood, and a desire to feel a connection to the food and not consume an industrial product. She knew where every product came from, its connection to the regional culture, and the history of it had evolved over the years.

“I found it very interesting to take part in the competition because I thought it was an important meal,” she said. “Breakfast is a gourmet meal, after all.”

A New Breakfast Hope

Walking the streets of Paris, one can catch glimpses of restaurants trying to embrace breakfast/brunch, though not always quite getting the full concept. Bagels are a catastrophe here, a bread that has been mistaken as a bun for sandwiches, too light and dry, and served at stores that may not open until after 10:30 a.m. Never order a bagel in France. It will break your heart.

As we’ve traveled over the last couple of years, we have noticed that many of the inns and B&Bs where we stay are starting to serve much more substantial breakfasts. Though, I’m not sure anyone in France can top the Château de Damigny in Normandy. No doubt accustomed to a heavy flux of American visitors coming for the nearby D-Day beaches, the morning breakfast buffet is next-level bonkers, including crepes, bacon, eggs, a basket of croissants, a cheese station, and an array of homemade jams.

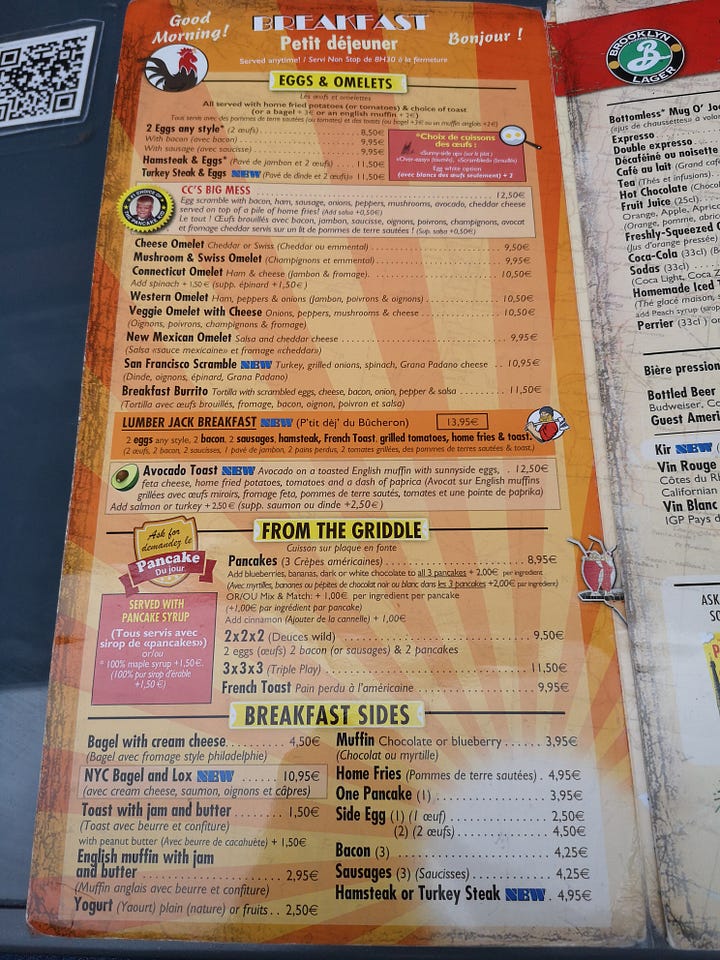

In the end, we satisfy our craving for diner-style American breakfast with an annual meal at Breakfast in America. Started almost 20 years ago by ex-pat Craig Carlson, BIA now has 2 locations in Paris. The breakfast is an honest-to-god breakfast. Bacon that is bacon, blueberry pancakes, eggs, and a bottomless cup of coffee. This is decidedly middlebrow stuff. Boxes of Aunt Jemima’s pancake mix line the shelves. It is certainly not the reason anyone moves to France. Yet it scratches the American breakfast itch in just the right way.

Still, the Best Breakfast Competition shows how the French could still win this whole breakfast thing. Plates that demonstrate the artistry and creativity that are possible by cooks ready to embrace the fundamentals of the Anglo-world breakfast but take it further and higher.

As an American who has been living in France for almost 10 years, this is the cultural revolution of my dreams. If the French are ready to overthrow the established order and man the brunch barricades at long last, I am ready to take up my waffle iron and march alongside them in solidarity.

Chris O’Brien

Le Pecq

As much as I enjoyed breakfast in the US, I was sort of haphazard about it. So, when I moved to France I got more used to things here and only very very rarely make anything approaching an American breakfast (bacon and eggs). I find that asking the local traiteur or boucherie to give you however many slices of lardon fumé is the same as bacon (it looks like it as well). Depending upon my mood I ask for thick or thin slices. It is delicious, and tastes like the bacon I had at my grandparents' places as a kid, not chemical-laden. One thing for breakfast I had often in the US was oatmeal. That has been difficult to get here that doesn't turn almost into paste when you cook it. For one thing, the flakes are often very tiny, but even when you find the large ones, cooking them they all stick together. Not sure why that is, but it is nowhere near as enjoyable as what I had back home.

I've never tried a "bagel" here in France, from your description it'd be about as horrible an experience as having "Mexican" food here. I liken it to something someone tries to make that they've never eaten, and had only seen in photos, using the wrong ingredients. Fortunately, I don't get cravings for it, or I'd have to learn how to make it (if I could even find the right cheeses and spices). And I 100% agree with you on coffee here. Such a disappointment! I haven't been able to figure out why, but I have my own espresso machine at home, and it churns out the good stuff. That's one thing the UK does better for sure, is morning coffee. I actually liked theirs more than what I got in the US. Again, not sure why, though I suspect part of it is the milk (I do put that in my coffee, but can't stand sugar in it or in tea).

All that said, I'm satisfied walking to one of the boulangeries here in my very small town of around 3000 kind people here in Normandie, where I have the luxury of 4 different boulangeries to choose from. Each has their specialties so I patronise them all. About the only other things that are difficult/impossible to find here is Sherry, Marsala, and natural peanut butter. But, those are small tradeoffs for the enormously better choices in most everything else one could want to eat (with the possible exception of steak, which I only very rarely had in the US). And I can easily get my favourite, duck, for relatively affordable prices. It's 1/3rd to 1/5th the price I used to find it for in the US.

Anyway, interesting article, I'd not heard about this push to aggrandir our breakfasts!