Hi-ho, The Derry-O, French Farmers Are In The Merde

A crisis building for years in the countryside finally erupts with a "siege" of Paris by rural protestors demanding more radical support for the nation's suffering farmers.

Outsiders can easily fall into the trap of thinking that Paris is France. That the nation is defined by its global luxury brands and artsy films and Haute couture and Michelin restaurants.

If they venture outside of the capital city, perhaps they will visit the urban centers of Lyon or Marseille or Cannes. For those adventuresome spirits who romanticize the French countryside, they are probably dreaming of the vineyards of Bordeaux or the lavender fields of Provence.

The reality is quite different. France is a farming country. Farms account for just over half of the mainland territory. Okay, it’s not Kansas (88% of the state is farmland). Still, France is the European Union's largest agricultural producer.

For a long time, French farmers managed to resist the rapid industrialization of farming that was sweeping much of the globe, particularly the U.S. where large corporations were consolidating farmland and family farmers were failing at alarming rates.

But that trend has taken hold in France in recent years with a vengeance. In the most recent agricultural census, the French government reported in 2021 that there were 389,000 farms — a sharp fall from 490,000 in 2010. The amount of territory used for farming, however, has roughly stayed the same. But average farm size increased to 69 hectares in 2020 from 55 hectares in 2010 as corporate agricultural machines gobbled up failing family farms. That is still smaller than the 332-hectare average for Canadian farms and 178 hectares for US farms, but trending in the wrong direction for French farmers.

The reward for family farmers who try to persist in the face of these forces is often a life of misery lived on the edge of constant financial precarity. When we lived in Toulouse, the local newspaper regularly published stories about extraordinary schemes people had put in place to save their farms.

There was the teenager who raised €230,000 in a crowdfunding campaign to rescue her parents’ farm in the Lot-et-Garonne department which was facing a crushing debt of €400,000. Then there was the farmer in the Tarn department who created a cabaret called Les folies fermières to bring in extra income.

These stories of heroic resistance were often overwhelmed by ones far more grim: A steady drumbeat of suicides. Between April and June 2019, 5 farmers committed suicide in the Gers Department, just west of Toulouse. A 2023 study indicated that suicide rates for people in the agricultural sector were 30% higher than the rest of the population. On average, one farmer commits suicide every day in France.

Agricultural Uprising

Against this backdrop, the sudden nationwide protests by the nation’s farmers are hardly surprising, even if they did seem to erupt spontaneously without immediate warning. There was no single trigger that explained the timing. Rather, mounting grievances boiled over into local protests that quickly became a national wave. One that is now washing over Paris.

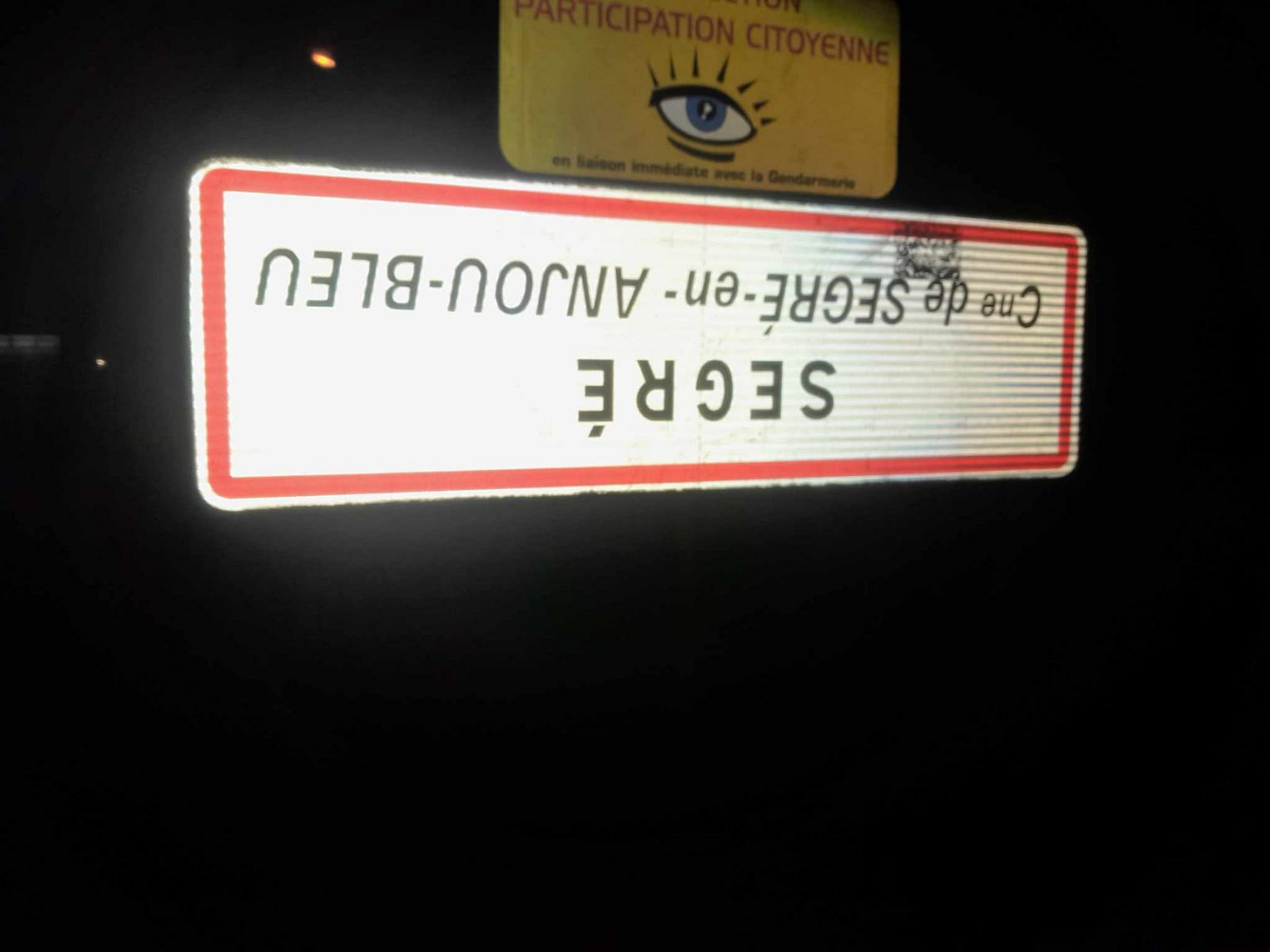

The protests began quietly. In late November, an association of young farmers began turning local street signs in rural areas upside down in a campaign called, “Nous marchons sur la tête” (We're walking on our heads).

Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne made some concessions to farming unions in early December by dropping plans to increase fees for water pumping and pesticide use designed to reduce agricultural pollution.

But it wasn’t enough.

The AFP reported that just over a week ago, Jerome Bayle set up a farming roadblock with some friends just outside of Toulouse. Bayle had recently taken over the family’s cattle farm after his father committed suicide. His example inspired similar actions across the country.

The complaints and demands are wide-ranging. Farmers are angry over the growing administrative requirements — paperwork, inspections, and increasingly complex rules. The government had proposed a gas tax to fight climate change that explicitly targeted use for agriculture purposes. They are upset at EU subsidies which seem to favor products coming from outside of France (the far-right has been eagerly exploiting this issue).

In general, farming unions say their members feel squeezed by government policies that require them to adopt more environmentally friendly practices while also producing more and keeping prices low. For French farmers, these mandates seem contradictory and incoherent. For instance, in recent months, consumers have been buying notably fewer organic products as prices soar, leaving farms that converted to organic in the lurch.

Target: Paris

Starting late last week, farming unions and associations made clear they planned to ramp up their protests by blocking major roads into Paris. Parades of tractors have slowly been making their way to the capital.

France’s new Prime Minister Gabriel Attal tried to calm the fury that greeted him when he took the gig a couple of weeks ago. He went to meet farmers at blockades, held meetings with union leaders and announced new concessions. That included withdrawing the plans for an agricultural fuel tax increase, administrative reforms to simplify procedures, and new financial support such as money for farmers who have to cull their herds in the wake of disease, €50 million for organic farmers, and a plan to oppose an EU agreement that would allow more beef to be imported.

The main French farming union, however, says it still falls short of recognizing the immense suffering of the nation’s farmers.

So on Monday, the tractors arrived and the blockades began around Paris, with at least 8 major roadways being shut down. The blockades are also happening around the country and in other EU countries. They are expected to last until Thursday when the EU is holding an agricultural-related session in Brussels. Protestors are saying they plan to take their blockades to Brussels next.

Among many issues, farmers are furious over an EU plan adopted in 2019 that calls for reducing the use of pesticides by half by 2030, cutting chemical fertilizers by 20%, and reducing the use of antibiotics for farm animals by half.

Defusing this crisis has no easy answers. The tension between climate change and the carbon footprint of farming has existed for years and still must be addressed. The structural issues facing family farmers are powerful. Policymakers will have to make impossible choices between cheap food and food sovereignty.

Time is running out to resolve those issues. Speaking directly to farmers several days ago, Attal said: “Without farmers, there is no country. I am convinced that a dialogue, even demanding and even sometimes harsh, is still possible in France. The work has only just begun.”

For farmers, it’s a painfully late start. If a new balance is not found, it’s not hard to imagine a France without family farmers.

Chris O’Brien

Le Pecq

One reason Montana has the highest suicide rate in the country -- too many guns to begin with, but ranching is so precarious -- one bad year when you're dryland farming wheat and you're wiped out. Like France, we have a big issue with rural suicides.

We also have the only actual farmer in the Senate representing us. He doesn't talk about it much, but Jon Tester was instrumental in building the organic legumes sector up in those dry lands, in part as a way to save $$ by cutting inputs, and rebuild soil because legumes.