The Opposite Of France

Visiting my hometown of Overland Park, Kansas

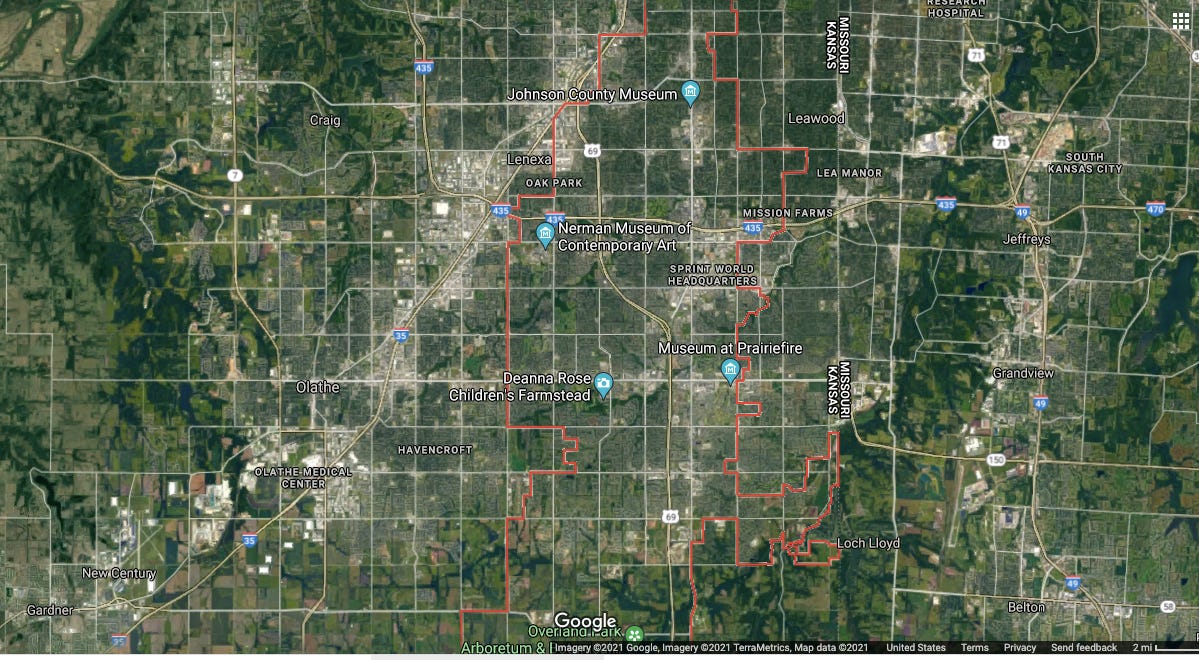

The photo above is a satellite image of Johnson County, which lies just southwest of Kansas City. I grew up in the city of Overland Park, which is the territory inside the red line. Last month, I returned to my hometown for the first time since I moved to France in 2014.

What’s notable about that photo are the white lines. This is not an alignment grid superimposed by Google Maps. These are the actual main roads. They are an almost faultless lattice of parallel and perpendicular streets that are the foundation of one the most well-planned suburbs in the history of suburbia.

The streets running from east to west are numbered, growing larger as one moves further south. When our family moved to our house on 102nd Street in the Oak Park subdivision in 1979, the suburban development stopped at 103rd street. Across the street, there was farmland that stretched more or less to the Oklahoma border. As kids, we used to cross the busy road to look at the cows across the street. Today, development stretches at least down to 387th Street.

This is typically what the world calls “sprawl,” often a synonym for suburbs that implies a kind of messiness and decay. As Arcade Fire once morbidly described American suburbia: “Living in the sprawl/Dead shopping malls rise like mountains beyond mountains.”

Overland Park and Johnson County, despite this relentless march south, do not have mountains of dead shopping malls, or much messiness for that matter. There is only one dead mall that I am aware of from my youth, Metcalf South, which died and was razed in 2017. My brother once worked at the Jones department store at Metcalf South selling women’s shoes of all things. Despite an abundance of other retail options in Overland Park, Metcalf South’s decline prompted great sadness among locals and gave rise to a surprisingly active Facebook group where people continue to share their memories of this shopping edifice. I suppose that in a suburban zone that is constantly striving to appear new, one takes what one can get in terms of ancient artifacts.

I have now been driving these streets again for more than a month. The strip malls zip by interspersed with perfectly manicured subdivisions. Even though most of this town didn’t exist when I was growing up, it all seems familiar. While I should be more cynical about all of this, the homogeneity and predictability are undeniably reassuring at this particular moment. It is impossible to get lost here. At least in the physical sense.

That serene feeling has brought into sharp relief the tradeoffs I have made as an adult in terms of where I’ve chosen to live. France represents a place of adventure, long cultural memory, and historic architecture. I love the chaos of France, the passion people have for living, the sumptuous food, and the rich culture. But it’s also an endlessly frustrating labyrinth, whether I’m navigating streets designed for horses that run helter-skelter, or life in general where the social and bureaucratic details are their own kind of impenetrable maze. I am constantly having to figure things out and find my way.

Since arriving in Kansas last month, it felt like someone had taken the yoke off my shoulders. Certainly, some of that is a factor of language and culture. There are not those additional layers weighing down on me. But at the age of 52, I can appreciate more than ever the appeal of orderliness and predictability, even if those values wouldn’t be seductive enough to lure me back to live here full time. At the same time, it’s impossible to ignore that many of Overland Park’s virtues also have come at a cost in terms of diversity and exclusion.

Still, in ways big and small, Overland Park feels like the opposite of France. That it also represents the perfection of the suburban ideal (for better and for worse) is not really surprising. Because this is also where the suburb was invented.

Jesse Clyde Nichols

William J. Levitt is popularly credited with shaping America’s Post World War II suburban evolution. His housing development, Levittown, offered low-cost homes in a development outside of big cities. But really, Levitt democratized a suburban concept pioneered by J.C. Nichols.

Several decades earlier, Nichols, a native of the Kansas City area, had a simple but powerful insight: As people bought more cars, they would no longer need to live where they worked. Rail lines had allowed some people to live further away. But cars would add even greater access and flexibility.

As people went to and from work in their cars, they could be enticed to stop and buy stuff. So Nichols created the Country Club Plaza which opened in 1923. Built in a Moorish Revival style meant to replicate Seville, Spain, the Plaza was effectively the world’s first strip mall, albeit an extremely stylish one.

Among its revolutionary features, the Plaza was the first regional shopping center with parking, a single architectural design, and a central management system for retail tenants.

The Plaza was situated between downtown Kansas City and the Country Club District, a new subdivision to the southwest that Nichols was building. Nichols worked with architectural landscapers, designers, and planners to create neighborhoods of exclusive homes set back on big lawns and tree-lined streets. He demanded gridiron layouts of streets, the grid-like pattern that has continued to propagate over the decades. To keep the aesthetic and to ensure the success of the Plaza, no retail was allowed in these subdivisions.

The other things not allowed in Nichols’ communities were African-Americans and Jews. Nichols used restrictive covenants to limit his developments to whites only. In addition to his use of strip malls and subdivision designs, these restrictive covenants also became a big part of Nichols’ legacy and were widely replicated across the U.S. in the 20th century.

Last summer, I followed from afar as that darker part of Nichols’ legacy finally caught up with him while the Black Lives Matter movement gathered momentum. In recognition of his racist policies, the Kansas City Board of Parks and Recreation Commissioners voted to change the name of the iconic local fountain that bears his name and change the name of a prominent street, J.C. Nichols Parkway, back to its original name of Mill Creek Parkway.

Naturally, because it seems my worlds are forever finding ways to collide, that fountain was originally sculpted by a French artist named Henri Greber. Built for a wealthy Long Island family, it was bought by the Nichols family and moved to Kansas City in the 1950s. Greber designed the fountain to symbolize 4 rivers: The Mississippi, the Volga, the Rhine, and the Seine.

Everything In Its Place

In terms of demographics, things have changed since Nichols’ day, but not by much. The latest census reported that Johnson County is 86% white, a figure about the same as the last census in 2010 and well above the 76% national figure.

Despite that original suburban sin and the lack of diversity, Overland Park is also not an enclave of right-wing extremism. The city is in Kansas's 3rd congressional district which in 2018 elected Sharice Davids to Congress. Davids was the first openly LGBT Native American elected to Congress. She was easily re-elected in 2020 when the district voted for Biden over Trump.

In fact, lack of extremism and offensiveness is perhaps best describes how I see the city now. Architecturally, Overland Park is a hot spot for low-rise retail and office space, with no structure really begging to distinguish itself. The amount of retail seems improbably large making it impossible to imagine that there are enough people to support all this shopping. And yet, somehow it has achieved an equilibrium between retail and residential that makes it work on a macro scale.

Even as developers fill every inch of green space with more stuff, traffic flows smoothly in both directions all day. Locals like to complain about rush hour traffic that slows their commute by 5 to 10 minutes, but that’s only because they have never seen real rush hour traffic in places like L.A. and the Bay Area.

While “charming” may not be evoked here very often, our subdivision today looks even better than when we moved here from Chicago 40 years ago. Houses have been kept in immaculate condition. Lawns are neatly mowed every few days. I find myself bristling irrationally when I pass the odd yard pockmarked with dandelions, wild grass, and other signs of untidiness and sloth. This is Overland Park’s version of patrimoine, and the neighbors invest in its preservation accordingly, hinting at the wellspring of pride that flows strongly along these streets.

Things are not flashy here in terms of retail. This was for many years the corporate headquarters of Applebee’s restaurant chain. Sprint’s corporate headquarters was in Overland Park until it was devoured by T-Mobile. Otherwise, the largest employers are school districts and local governments. The local economy is a mysterious mix of service jobs that never gets too hot or too cold. The expansion comes at a steady, measured pace that keeps it manageable in terms of building infrastructure like new schools.

As for the people, if you know Ted Lasso, then you know Overland Park. Creator and actor of this Apple+ TV show, Jason Sudeikis, grew up here and attended my rival high school, Shawnee Mission West, where he graduated seven years after me. Sudeikis is part of the amiable acting-comedy trio that is the pride as well as the face of Overland Park. That includes Rob Riggle, who was one year behind me at Shawnee Mission South. And Paul Rudd (Ant-Man), who also attended SM West and graduated the same year as me. Though I never met Rudd, I can recall high school friends who participated in Debate and Forensics (the inexplicable name for theater competition) speaking of his performance skills with awe. He was everyone’s nemesis and yet everyone loved him because he was immensely talented, pleasant, and wholly non-threatening. Rudd is the Overland Park of comedy acting.

All of this on paper sounds remarkably bland. It suggests the suburbs which Arcade Fire also described as a place to run away from because it suffocated those who were different:

They heard me singing and they told me to stop

Quit these pretentious things and just punch the clock

Sometimes I wonder if the world's so small

Can we ever get away from the sprawl?

Yet I never felt trapped or a sense of ennui growing up in Overland Park. I had an extremely happy childhood here, spending summers at the local public pool, riding my bike to friends’ houses, and working summer and weekend jobs in absurd places like Godfather’s Pizza (“A pizza you can’t refuse”), The Olive Garden (“hospitaliano!”), and the Land of Ahhhhs (selling hot tubs in Kansas). Even though I did leave, first for North Carolina, and then California, and now France, it was more from a sense of wanting to explore rather than escape.

I certainly understand why so many others stayed. No doubt my attachment to my hometown is the product of nostalgia, friends, and family. Yet it’s more than that. Unlike France, Overland Park is built for the modern world, designed to facilitate movement and constant renewal.

Overland Park may not be exciting. But it is comforting.

I can relate to your feelings about being back. I feel something akin to that every time. It's hard to believe it goes all the way to 300 and something-th street now. Thanks for the great writing.