What Applying For French Citizenship Taught Me About The U.S.

On a late July morning, my wife and I walked down the street from our apartment in Toulouse to the Prefecture for our French citizenship appointments. The 5-minute trip took us past rows of the familiar brick façades that give our adopted home its nickname, La Ville Rose (Pink City), before arriving at the Prefecture.

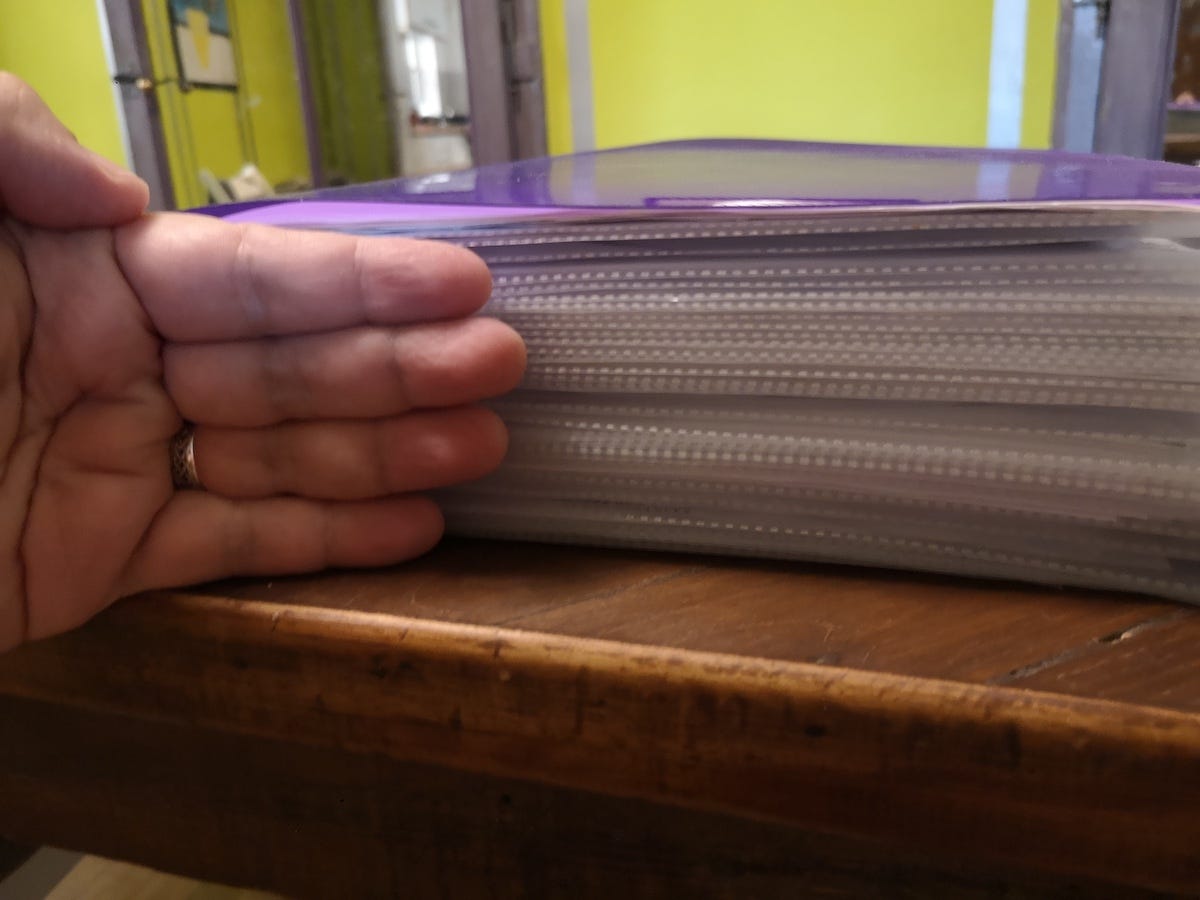

My wife’s meeting came first, and then 90 minutes later it was my turn. I sat across the desk from a middle-aged woman whose casual dress and warm demeanor helped put me at ease. A large plexiglass screen separated us, and I did my best to speak French loudly and clearly while wearing the required mask. On my lap sat my binder that had swelled to four fingers thick thanks to the long list of family and financial documents we had spent a year gathering to support our applications.

While preparing those dossiers, we had intensely reviewed our knowledge of French history, culture, and geography to ensure we could demonstrate that we had truly embraced life in our new homeland. After 30 minutes of handing over the documents one by one, it was time for my interview. Applicants can be asked any one of hundreds of questions: Name all the presidents of the 5th Republic. Describe an event that marked the history of France. Who are some famous French athletes? Who wrote La Marseillaise? Though I have dutifully learned the French national anthem, she mercifully did not ask me to sing it.

These questions can vary from candidate to candidate, but there is one everyone is asked: Why do you want to become French?

In response, I cited some of my favorite aspects of France: A pace of life that celebrates the savoring of moments, the extraordinary hospitality and friendship we have experienced, the food, and the joy of discovering this nation’s rich culture. But mostly, I talked about the third part of France’s motto: liberté, égalité, fraternité.

The U.S. shares with France a tangled history of revolutionary influences and political identity, including those first two words, “liberty” and “equality.” We hear this in the Pledge of Allegiance referencing “liberty and justice for all,” the national anthem that praises the “land of the free,” and the Declaration of Independence which promises “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” because “all men are created equal.”

What the U.S. lacks at its political and cultural core is “fraternity.” While the motto E pluribus unum (Out of many, one) suggests some vague sense of unity, it hasn’t become a cornerstone of American identity in the same way fraternity remains a bedrock of modern France. In the 6 years since we moved from California to this southwest corner of France, we have found that so many of the things that we deeply love about this country flow from its embrace of the common good.

Fraternity fundamentally means creating a structure that allows people to take care of each other. As part of the naturalization application, we had to study the Livret de citoyen (Citizens’ Book) which explains fraternity like this: “France is founded on the will of French citizens to live together. This means solidarity among citizens.” We also had to sign France’s Charte des droits et devoirs du citoyen français (Charter of Rights and Duties of the French Citizen) to signify that we agreed to live by this nation’s values. In the fraternity section of that charter, it makes our obligations clear.

“Everyone has a duty to contribute, according to their financial capacities, to the Nation’s expenses by paying taxes and social contributions,” it says. This is part of a pact. In return, the charter promises: “The Nation guarantees to all the protection of health, material security, and the right to vacation. Anyone who is unable to work by reason of one’s age, physical or mental condition, economic situation, has the right to obtain an adequate means of subsistence from the community.”

This contract between the state and the individual makes the relationship clear: You pay taxes and in return, the state promises to take care of you. And the state being “of the people,” the state is then a vehicle by which people take care of each other. Naturally, most Americans tend to ask us about the first part of the bargain: “Aren’t the taxes in France really high?” People almost never ask what we get in return.

Fraternity manifests itself in the wealth of public services in France. Schools are funded and don’t require weekly bake sales to pay teachers’ salaries. Vibrant cultural institutions aren’t begging for donations. Municipal summer camps for our kids cost a fraction of the fees we paid in the Bay Area. Public transportation is reliable and affordable. The main complaint we hear is that the state should be doing even more in these areas.

Perhaps most notable is the national healthcare system. Watching the U.S. continue to tear itself apart over this issue is heartbreaking. It’s also unfathomable to our French friends, who continually ask us, “How can some people not want other people to have health care?” In the U.S., the topic turns around the notion that such a collective system would impinge individual freedoms (choosing a doctor) and require taxation (the horror!). The benefits tend to be shuffled aside.

For so many Americans, the individual remains paramount, a growing cultural selfishness. The U.S. government is no longer an expression of the people, but rather a separate enemy to be fought and subdued. This rejection of the government is also a rejection of one’s fellow citizens, both to help them and to be helped by them. From a distance, it’s painful to watch the tragic ways the absolute desire for individual freedoms continues to impede any attempt to work collectively, particularly during the COVID-19 crisis. The protests against wearing masks are perhaps the perfect manifestation of how individual desires for “freedom” have been elevated over the collective good.

France’s response to the pandemic has not been perfect, and even now we’re just emerging from a second lockdown. But when the coronavirus raged this spring, the government imposed a strict lockdown that lasted two months. We could only leave our apartment for one hour per day and had to sign a document stating our reasons. City streets emptied. Everything stopped. It was painful but made endurable by a strong sense of solidarity. We were all in this together. The second lockdown is certainly testing that solidarity, but it has for the moment slowed the spread of the virus. And while many French wish the government was doing more economically, the financial support packages have exceeded those of just about every other European country.

I won’t pretend that France is a utopia. Certainly, this nation has its share of challenges and political divisions over issues like the economy and immigration. For more than a year, the Yellow Vest movement dominated politics with weekly protests against the government.

But in its way, this explosive social movement reinforced that notion of fraternity. While a gas tax helped spark the Yellow Vests, who came to encompass a wide range of grievances, fundamentally participants were angry that the government wasn’t doing enough for them. They wanted more assistance navigating the economic impact of globalism, particularly in rural areas suffering from a lack of jobs, infrastructure, doctors, and reliable public transportation. It was a sharp contrast to the U.S. Tea Party uprising, to which it has been compared at times, that wanted lower taxes and less government.

During the Democratic Convention, Sen. Elizabeth Warren recalled the days when she was struggling to juggle childcare and her teaching job. Her aunt saved her by moving in to take care of the kids. Warren used the anecdote to make the case for affordable preschool, something that France offers for free from the time kids are 2 years old. She also offered a more basic lesson: “I learned a fundamental truth: nobody makes it on their own.”

In the U.S., many would dismiss this notion as some sorry excuse for socialism. To me, it seems like such a basic human truth. Let’s take care of each other. We are all in this together.

I did see some small glimmer of hope amid the current chaos in the U.S. that attitudes might be changing, and on Fox News of all places. On August 13, the conservative channel released a poll that found 57% of respondents wanted the government to “lend me a hand” compared to 36% who wanted it to “leave me alone.” That was a big turnaround from February 2019 when 34% wanted government help and 55% didn’t.

No doubt these people want concrete things like financial relief and help fighting the coronavirus. Less consciously, they are expressing a desire for more of the fraternity that we have experienced in France. If Americans are indeed open to learning this modest lesson from their French cousins, then it could perhaps be a first step toward restoring faith in government and one’s fellow citizens.

I agree with everything you said. We lived in Southern Burgundy from 2000 - 2020. We sold our home and little guest house and moved back to the states. What a mistake! During this horrible time in the states, we do miss our precious village so very much. And have tried to spread the good words you said about how France works, compared to the states. We talk about this all the time in our little local France class and our American friends in it realize why we pay taxes. And appreciate the aid they give to those citizens who need it. I also agree with the word you used "selfish". We changed a lot of our views about the USA during the first year or two. Quite an education, huh?

So true. I became French via my mother, so no effort there on my part, but I chose to live in France for most of the reasons you chose to become French. Toulouse is also the city where I first discovered France as student in the 1970s, one of my favorite cities, still.