Once Upon A Time In France: War Of Words, Exterminating Extremism, And Food Fights

Dreaming of Auxerre

We’re moving into the second week of our February vacation from our perch in the Paris suburbs and the weather has turned downright tropical by French standards. But while the weather was still gloomy last week, we opted to celebrate as any good American family would: By going to Costco.

There is only one Costco in France, and it was a 45-minute drive from the western outskirts of Paris. Once inside, it felt like the supremely American experience, offering an intense, cultivated shopping experience that bends one’s psychology toward making purchases that seem incomprehensible after the fact.

As I write this, I am staring at two enormous bottles of Hershey’s chocolate syrup, an item we have never purchased as a family over the past 25 years. It’s impossible to recall the brief fever dream that compelled us to buy these jugs of liquid chocolate. We could make sundaes every day until the pandemic ends and still not use all of it. Meanwhile, the family also acquired a healthy supply of real American Mac & Cheese, a 6-pack of Ritz cracker boxes, 18 pairs of socks, 6 liters of coconut water, and an industrial-sized package of frozen mozzarella sticks.

The receipt was longer than my arm. And it didn’t include a stop at the takeout counter where we bought an honest-to-god pepperoni pizza. I mean, real pepperoni and not this chorizo nonsense that masquerades for pepperoni in France. It was a shopping trip that felt like a cultural renewal of my American-ness, which at its most basic seems to involve the unbridled acquisition of stuff because it seems like a great deal even if later one stares at these purchases sitting on the kitchen table and feels utterly stupefied.

I suppose all people feel some instinctual need to recognize and protect their culture. That was no doubt the case for François Jolivet, a deputy of President Macron’s LREM party who has proposed a new law that would ban “l’écriture inclusive” in all official administrative documents.

Écriture inclusive is an attempt to make the French language more gender-neutral. By calling it out for being inherently sexist because it favors the masculine usage. Proponents have outlined a complex, if awkward, remedy that its adherents argue is essential for correcting the subtle ways the French language creates stereotypes that are biased toward men over women. Given the profound role gender plays in the French language, untangling that knot is tough.

For Jolivet, according to the Charente Libre newspaper, inclusive writing is a "personal and militant" choice which "scrambles the messages" and "makes learning the French language more complex."

On a very basic level, inclusive writing proposes three main solutions. The first is probably the most straightforward and easiest to digest. Where possible, replace general phrases that refer to something about “man” (“homme”), with a gender-neutral word, like “human.” My kids have spent a fair amount of time learning about the “Droits de l’Homme.” (“Rights of man.”) Instead, use “droits humains”. Simple, except of course “humain” is a masculine noun. So then maybe try “droits de la personne humaine.” Because “personne” is feminine, which lets you change “humaine” to its feminine form when used as an adjective. Phew.

French is like the old briar patch when it comes to gender: The more you struggle against it the more you become stuck.

The next option is to use both forms. For instance, you can say, “Elles and ils font” (masculine “they” and feminine “they” make). It’s not uncommon now to hear a speaker in public begin by saying, “Bonjour à tous…et à toutes.” Or you can try “les membres” (which is still masculine).

For certain words that tend to be the same for masculine and feminine, make greater use of the feminine option. Still, even this can be confusing. For instance, a man or woman who teaches is a “professeur” according to official usage. However, a separate guide d'aide à la féminisation des noms de métiers published in 1999, according to Le Figaro, allows use of “la professeure” for the feminine.

Then comes the l’écriture inclusive whopper, the one that really ties certain corners of the country in knots: Take a word and include all the possible endings with extra punctuation. So “candidat” (masculine) becomes “candidat·e·s.” Admittedly, it’s awkward to write, and it’s anyone’s guess as to the pronunciation.

Language remains a serious affair in France, where something as trivial as the introduction of a foreign word into casual speech can spark furious public debates among intellectuals as well as regular folks on social media. So one can imagine the backlash something like l’écriture inclusive has provoked.

More than three years ago, the issue was in the national spotlight after the publication of the first gender-neutral textbook for elementary schools that embraced écriture inclusive. One of the groups behind this movement is called “Mot-Clés” (“Key Words”) which has described French as a “phallocentric language” and published instructional material on how to write anew in a way that will motivate a more fundamental shift. “To really change mentalities, we must act on what they are built on: language,” says its website. Even for many on the left, it poses an uneasy choice between their belief in progressive ideas about men and women and their passion for language.

The ensuing hysteria following the book’s publication was perfectly captured by l’Académie française, the organization charged with adjudicating all things related to the French language for the last four centuries or so. The academy is one of those elements of French culture that seems like it was invented by someone who wanted to write a parody of French culture. It is presided over by members who are called “the immortals”, and each one looks like they responded to a casting call for actors to play the most extreme caricatures of stuffy, conservative, reactionary, and humorless French elites and intellectuals. In late October 2017 the immortals declared that inclusive writing posed a “mortal danger” to the French language. They warned that inclusive writing could make French so complex that it could fall from favor by causing people around the world to learn other, more barbaric languages that were easier.

“In the face of this ‘inclusive’ aberration, the French language is now in mortal danger, for which our nation is now accountable to future generations,” they huffed. “It is already difficult to acquire a language, how will it be if the user adds to it second and altered forms? How will future generations grow in intimacy with our written heritage? As for the promises of the French-speaking world, they will be destroyed if the French language weakens itself by this increase in complexity, benefitting other languages that will take advantage to prevail on the planet.”

I have some bad news for them on that latter point. But I’ll save that for another time.

Exterminating Extremism

Speaking of culture wars, France is preparing to look into how “wokism” has infiltrated French universities. This follows months of growing tension around the notion that American culture is corrupting France with concepts such race-based analysis of social issues.

According to The New York Times:

Frédérique Vidal, the minister of higher education, said in Parliament on Tuesday that the state-run National Center for Scientific Research would oversee an investigation into the “totality of research underway in our country,’’ singling out post-colonialism.

In an earlier television interview, Ms. Vidal said the investigation would focus on “Islamo-leftism’’ — a controversial term embraced by some of Mr. Macron’s leading ministers to accuse left-leaning intellectuals of justifying Islamism and even terrorism.

“Islamo-leftism corrupts all of society and universities are not impervious,’’ Ms. Vidal said, adding that some scholars were advancing “radical” and “activist” ideas. Referring also to scholars of race and gender, Ms. Vidal accused them of “always looking at everything through the prism of their will to divide, to fracture, to pinpoint the enemy.’’

The exact meaning of “Islamo-gauchisme” is a bit fuzzy and controversial, but it seems to be a kind of stand-in for “woke” though obviously, it also hints at some unnatural sympathies among the left with Islam.

While trying to outflank the left, the government is also cracking down on the far right.

Last week, Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin announced the beginning of a legal procedure that would formally dissolve a right-wing anti-immigrant group known as Génération Identitaire. The group is accused of “provoking public racial hatred,” according to Les Echos. Most recently, the group was patrolling the Spanish border in the Pyrénées waving banners that read “Defend Europe” and using drones to catch sneaky immigrants.

This move toward dissolution provoked a demonstration this weekend in Paris by members of Génération Identitaire. Huffington Post noted:

Demonstrators chanted “We are at home!” Others brandished “Dissolved because of identity” signs, while some sported caps with the slogan “Make America Great Again”, similar to those worn during the Donald Trump's campaign in the United States.

"Our French culture and our European civilization are threatened by immigration," according to one speaker at the march. “It is not Zidane or Omar Sy who enrich France but France which enriches them."

Food Fights

On a (somewhat) lighter note, France has reformed a law that effectively forbids French employees from eating lunch or dinner at their desks. The motivation is Covid, and the rule change is temporary, according to The Local.

Meals are intensely social moments, even at work, in France. When I first began working at some co-working spaces, I was surprised that just about everyone would stop working at 12:30 p.m. and gather in a break room with whatever food they had prepared or bought to eat together.

In contrast, I felt deep anxiety taking an hour-long break. I just had too much work to do! And I soon realized that I was the only one nibbling snacks at my desk between meal times, a practice I soon stopped. Even the giant Starbucks coffee perched on the desk for several hours was a non-starter. If you wanted a coffee, you got up and went to the espresso maker and made it and drank it.

I’ve learned to appreciate this over time. Eating and working remain another quintessentially American habit. If it permanently takes hold in France…they may never forgive us.

Traditional French eating was also under siege in Lyon, where the local Green Party government decided to implement a vegetarian menu in some school cafeterias.

Interior Minister Darmanin was not amused.

“In addition to the unacceptable insult to French farmers and butchers, it is clear that the moralist and elitist policies of the ‘Greens’ exclude the working classes,” he tweeted. “Many children often only have the canteen to eat meat ... Scandalous ideology.”

Dreaming Of France

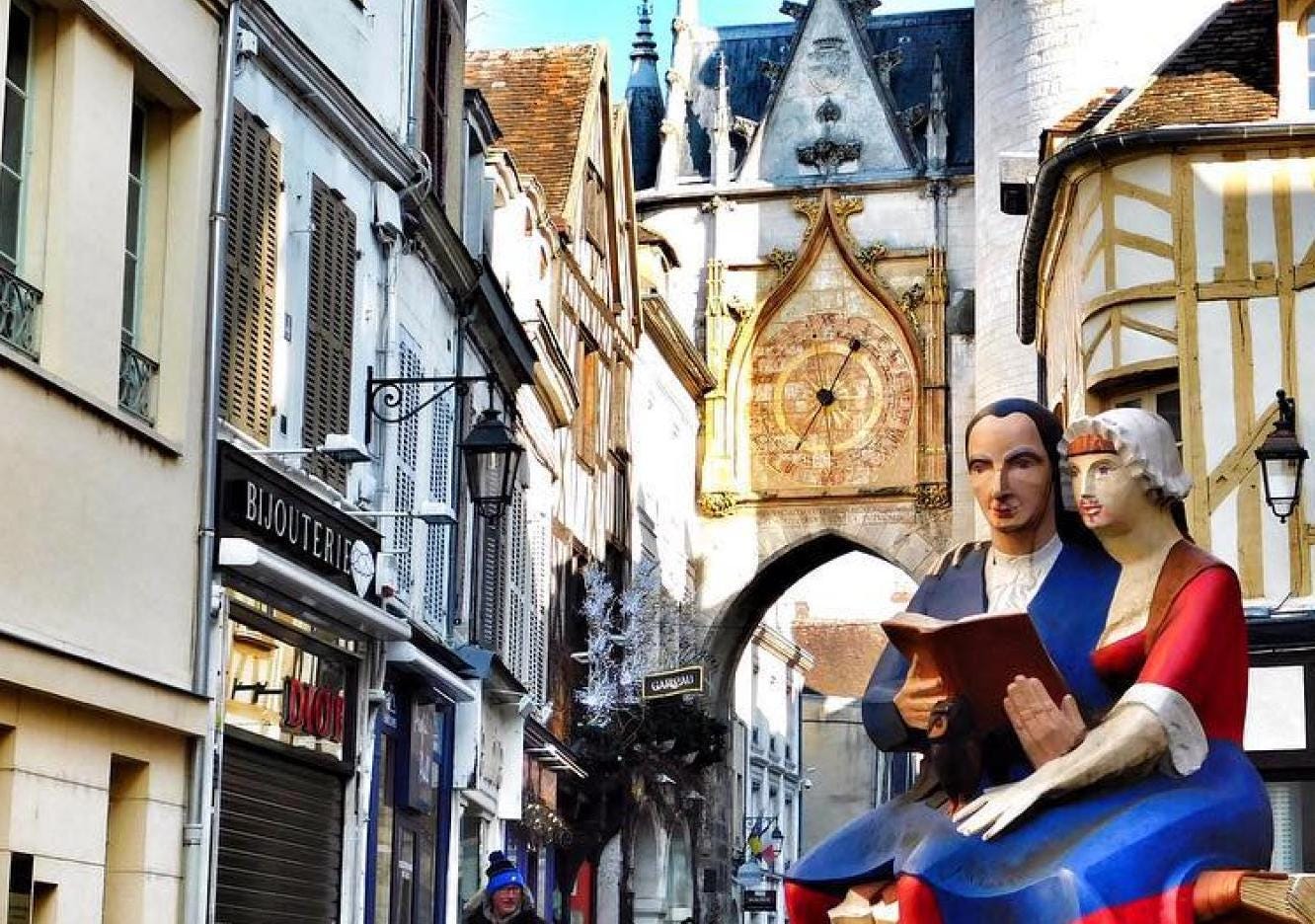

Just 90 minutes southeast of Paris, the city of Auxerre (pronounced Aussere) is located in the Yonne Department and the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region. Or, what is simply known to most English-speaking visitors as the Burgundy region.

Auxerre’s highlights include the Abbey of Saint-Germain d'Auxerre sitting along the Yonne River, just one of several churches in the town worth visiting. The Medieval city center features a stunning astronomical clock. The city has both a natural history museum and a digital arts museum. And, of course, its many local restaurants allow visitors to experience Burgundy’s famed culinary delights.

But Auxerre, Burgundy’s fourth largest town, is also a great jumping-off point to explore the region’s famed vineyards, including Chablis, and a series of other small, historic villages such as Vézelay and Noyers-sur-Serein which are often ranked among the most beautiful in France. The Yonne River and the Canal de Nivernais can be enjoyed by boat, bike, or on foot.

Put it all together, and there is plenty in Auxerre for anything from a quick day-trip to an extended stay to really appreciate Burgundy.

Great Reads

The reconstruction of Notre Dame in Paris is proceeding. But in a story over the weekend for Forbes.com, I noted the latest challenge:

The 2019 fire that ravaged the Notre Dame cathedral in Paris has forced officials to make a number of difficult decisions, including how to replace the spire that was destroyed in the blaze. Having chosen to rebuild the spire to match its classic design, the nation now faces a new and controversial chore: Where to find all that wood?

According to Le Figaro, forestry teams are scouring the Conches and Breteuil massif, in the Eure region to find oaks that must be between 150 to 200 years old. Time is running short. President Emmanuel Macron had set a goal of rebuilding the spire by 2024. But the trees would first need to dry after being cut for between 12 to 18 months.

In other news, small towns in France are continuing to build new movie theaters as part of an economic revival strategy. A French woman, who lost most of her family in the Holocaust, is fighting a complex legal battle with the University of Oklahoma over a Pissaro painting that was stolen from her father by the Nazis. And a French publisher is releasing some new, recently discovered writing by Marcel Proust.

Chris O’Brien

Toulouse, France